|

The gArab fs Spring h, which began in 2010 in the Middle East, achieved the success of the Civil Revolution in Tunisia, Egypt and Libya, overthrowing their governments. While in Syria, the president al-Assad has not stepped down, making the country a quagmire of endless civil war. People in the world must want to avert their eyes from its disastrous state, which on the contrary makes me feel the necessity to show how the land of Syria was culturally (architecturally) during its past peaceful days.

It was in 1980 that I first travelled to Syria in its peaceful epoch, getting attractive impressions, but my camera (Nicon F2 at that time) broke down without finding a capable repair shop in Syria, so I revisited there to take photographs of its superb monuments six years later.

In those days, Hafez al-Assad, the father of current president Bashar al-Assad, was the president of Syria. He ruled the country for nearly 30 years till his death in 2000, naturally strengthening his heavy-handed politics. In order to annihilate the eMuslim Brotherhood f that had risen in revolt, he thoroughly destroyed Syria fs fifth largest city Hama, considering the city as its base. The number of citizens sacrificed by the assaults of his army is said to have been 20,000 or 40,000, which is called the eHama Massacre f.

One of the architects participating in the repair of the Azem Palace told me that he was aiming for the restoration of the Great Mosque and the streets of the old town, but they did not have the drawings of their original states. Based on photographs only, I am not sure they could achieve it or not.

Syria of those days gave me the impression of being a police state with the experience of being took to a police station when taking photos of the cityscape of Damascus from a pedestrian bridge, though such affairs are not rare in developing countries. In India and Iran too, I was brought to police stations and the films in my camera were nearly confiscated.

Although Syria can be called an Islamic country like the others in the Middle East, its architectural legacy is not limited in Islamic ones.

Greater Syria was in a difficult geographical position put between large Empires of ancient Rome and Persia and had a long mutable and complicated history politically, religiously and militarily as an area that gave birth to important religions of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. It was in the modern times that it formed the independent country named the Republic of Syria, while in the past it was not a state-name but a term for some broad area.

Syria fs western region is conversely a fertile agricultural land, where various civilizations were born and collided with each other from ancient times. This historical evicissitude f surely fostered its cultural variety as the fountain of Syrian architecture fs attractiveness. Its outcome was not eearthen houses f but high-grade stone architecture.

It was Egyptian Civilization that developed stone architecture at the very beginning, the next was Persian, while Assyrian Civilization, from which derived the name of Syria, flourished in Mesopotamia around current Iraq and its edifices were made of earth, i.e. sun-dried bricks, the material not tending to remain as ruins, so most of them returned to the earth after the fall of the civilization. In ancient times Phoenicians built city states on the Syrian east coast of the Mediterranean, leaving a very few remains. It might be said that the temple of Amrit is one of the ancestors of Syrian stone architecture. Based on ancient Greek architecture and under the influence of Oriental (especially Persian) architecture, the Roman Empire developed large-scale stone construction with the full use of arch and dome structures, which had not been known by the Greeks. This is called Hellenistic architecture. In Syria too, as ruled by Rome, there remain plenty of Hellenistic Roman monuments in Palmyra, Bosla, Apamea, and so on. When Christianity rose, gradually spreading from Syria-Palestine to the Roman Empire broadly, its church buildings borrowed the form of Basilica from ancient Roman architecture, that is, a rectangular edifice with two or four rows of columns inside and at the center of one side is a semicircular apse jutting outside. It was mainly used for people fs assembly halls or courthouses in Rome, and became the religious building fs form, placing altars on their apses.

Such early Christian churches and the followers f hamlets were constructed in Syria in several hundreds, a large number of which still remain as ruins of stone heaps.

In the 7th century was borne Islam in Arabia by the prophet Muhammad and Syria became under its control in a twinkle. During the period of the Rightly Guided Caliphs (632-661) after the death of Muhammad, Islamic power became the Arab Empire, totally conquering Persia, Syria and Egypt. And then the Umayyad family took power, founding the Umayyad Dynasty (661-750) based in Damascus in Syria as its capital. In the age of Romanesque culture in Europe, the crusaders suddenly came and invaded Syria, establishing the Kingdom of Jerusalem to colonize it. Their castles, churches and monasteries were erected in Romanesque style, among which the castle of Krak des Chevaliers, the best preserved medieval European citadel, stands on a hill commanding a distant view of the Mediterranean Sea. As the buildings in its premises were constantly maintained, the additional part constructed in the 13th century is in Gothic style. It was Salah al-Din (1138-93), the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty, who defeated the crusaders. He was respected even by his European enemies, through the abbreviated name of Saladin, as not only a brave warrior but also a wise and righteous monarch. Architectural works in the Ayyubid era are left many particularly in the second largest city of Syria, Aleppo. However, Syria was not able to be independent afterward, obeying the Mamluk dynasty in Egypt after the 13th century and the Ottoman dynasty in Turkey after the 15th century. Therefore, its buildings were in the Egyptian fashion during the former era and in the Turkish fashion during the latter. There is also a work of Sinan, the greatest Mimar (architect) in Turkish history, in Damascus. As seen above, Syrian architecture shows incessant vicissitudes under the influences of neighboring civilizations, but when looking through them conscientiously, the consistent eSyrian architecture f emerges through various styles on the surface of its history. It is, above all, the excellence of their skills in treating stone. Even if the buildings f scale is not so grand, it is an architecture of finesse and subtlety with exquisite details carried on every corner of its stone works.

(02 /09/ 2012) AMRIT Al Melqart Temple, 6th c. BC

Phoenicians made city states around the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea (western Syria to Lebanon) after the 15th century B.C.E. Amrit was its religious center with the ruins of Al Melqart Temple, which was influenced by Achaemenid Persian architecture and others. This temple is said to have still been functioning, when Alexander the Great came here in 330 B.C.E. Melqart was worshiped on identification with Hercules in the ancient Greek era, but Amrit was abandoned in the Roman era. PALMYRA Colonnaded Street & Amphitheater, 1-3rd c. BC

The city of Palmyra thrived from the second century B.C.E. as a transit point of caravan routes of east-west trade, located at the center of the Syrian Desert, just like the later city of Jaisalmer, at the center of the Thar Desert, India, flourished as a trading city. In contrast to Jaisalmer that survives still now, far more ancient Palmyra was destroyed by Rome in the age of Zenobia, Queen of the Kingdom of Palmyra, in the 3rd century. The extant magnificent remains of the city of Palmyra are from those days.

The Temple of Bel, Semitic god of fertility, stood in the square precincts of side 200 meters, originally being a peripteral temple, yet lost then having three sides. As well as Bel, it also enshrined two other gods: sun god Yarhibol and moon god Agribol.

The Temple of Baalshamin is a small but elaborate building, the origin of which goes back to 17 C.E. but the extant feature is thought to have been made in 132 on the whole, just after the visit of the Emperor Hadrian. The temple resembles the early Indian stone temples (in the 5th century), such as the temples in Sanchi and Tigawa, in terms of scale, single room plan, and existence of a wide front porch.

To the west of Palmyra is a necropolis called the eValley of Tombs f, where dozens of tomb towers and underground tombs are scattered. The best-preserved ones, restored in the 20th century, are the tomb tower of Elahbel and that of the Jamblichu (Iamliku) family. Their inside have one to five floors, of which the ground floor is the main tomb hall while upper floors also enshrine many tombs, without roofs. In the 'Tomb of Three Brothers' remains a fresco. Cardo (Main Colonnaded Street) 2nd c. Apamea typically shows the fundamental composition of ancient Greek and Roman cities. The city (Polis) is penetrated straight north and south by a magnificent colonnaded avenue, which was referred to as eCardo f, and its intersecting roads eDecumanos f. At the center of the city is a public square (Agora), on the hill is the citadel (Acropolis), and at the foot of the hill is an amphitheater (Theatron).

Since I felt unwell in Apamea soon after beginning the photography, I was not able to take enough photos of the city remains.

Amphitheate, 2nd c. BC

The best remains of Roman cities worth seeing in Syria next to Palmyra is Bosra, mainly owing to the large amphitheater best preserved in a perfect form. The Roman Empire directly ruled over the Arabian region from the early 2nd century, making Bosra its central base, into which it sent many troops. The city of Bosra rapidly thrived and even constructed a great amphitheater.

Bosra, the northern important city of the Nabatean Kingdom, the capital of which was Petra, is located near the current border of Jordan and has many remains of ancient buildings from the Roman to Islamic eras, though not well enough being preserved apart from the amphitheater. Among its city gates, the western one called the eBab al-Hama (Gate of Wind) is the best preserved.

QALAAT SEMAAN Saint Simeon's Monastery, 480-90.

The Roman Empire officially approved Christianity in 313 through the Milan decree, before which the earliest church buildings had been erected in Syria-Palestine and Constantinople. The notable Saint Simeon fs Monastery was in Qalaat Semaan in Syria, the church of which was built around the pillar of St. Simeon the stylite after his death in the fifth century. Since Christianity had become the national religion of the Roman Empire in 350, priests and followers were able to live peacefully, but there were pious ascetics desiring the life of true faith in the imitation of Christ. Some, like St. Antony, went to Egyptian deserts while others went to Syrian mountains.

The most peculiar among them was Simeon, who was born in c.350 and went alone deep into the mountains near Aleppo after the experience of a communal monastic life. He erected a stone pillar to mount on top every da as the nearest place to God and worshiped him, avoiding the disturbance of people who wanted his blessings. The pillar was re-erected many times, increasing the height up to 16 or 19 meters.

Basilical Church, 5-6th c.

To the west of Aleppo, the church ruins of Qalb Lozeh are located in a far more remote place than St. Simeon fs Church of the previous section, in a landscape of continuous rocky mountains like depicted in Russian icons. Along with St. Simeon fs, the church-design anticipated Romanesque architecture six centuries later in Europe, based on semicircular arches.

Christian Town and its Church, 4-6th c. On the hilly lands in the west of Aleppo are many ruins of towns and churches from the early Christian periods. They were from the 4th to 6th centuries overall. While wooden or earthen towns would disappear, stone towns and edifices remain as ruins. Kirk Bizeh is located about 1km north of Qalb Lozeh in the previous section along with numerous wreckages of buildings, most of which cannot be ascertained as to in what functions they served originally. However, the 1200 to 1300-year-old hamlets, composed of venerable grey stones only, display a mysterious and attractive air. In the book of Ignacio Pena gThe Christian Art of Byzantine Syria h are recorded many of such hamlet-ruins.

Cathedral Church of St Sergius, 559

Rusafa, located 50km southeast of Raqqa, was the forefront Roman city to do battle with Sassanian Persia. As shown by its old name eSergiopolis f, it was also the sacred city apotheosizing Saint Sergius, the church of which drew a large number of pilgrims. Since a Roman soldier, Sergius, refused to sacrifice animals to the Roman god Jupiter, he was persecuted by the Emperor Diocletian to death in 305 at this place.

The northern gate on the ramparts encircling the holy place of 550m x 400m is very luxuriously embellished with Corinthian columns and decorative arches despite its small scale. In contrast with the ruined environs, only this gate survived in such a good state, possibly because of the existence of a courtyard surrounded by small buildings in the front side, this gorgeous back side would have been overlooked. Basilical Church & Palace, 6th c.

The remains of Qasr Ibn-Wardan, located 62 km northeast of Hama, consists of a Byzantine church, a palace and barracks. The ensemble was built in the age of Justinian perhaps during 561 and 564. Although the church is based on a basilical plan, it is said to have had a 20-meter high dome in the past. It is impressive that the ensemble fs outer walls have a common feature of stripes with alternate wide black and beige basalt layers. The barracks have completely collapsed. DAMASCUS Umayyad Mosque, 706-715

After Islam was born in Arabia in the 7th century, its power formed the Arab Empire in a short span of time, conquering the overall Middle East from Egypt to Iran. Its first hereditary dynasty, established by the Umayyad family in 661, made Syria fs Damascus its capital city and constructed the great eUmayyad Mosque f there, which is to be called the first piece of Islamic architecture.

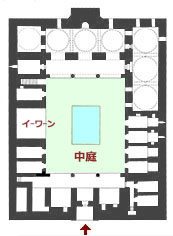

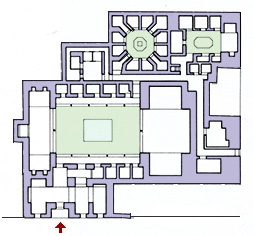

Plan of the Umayyad Mosque Great Mosque (Jami al-Kabil), 715, 12th c.

This Great Mosque of Aleppo is also the earliest piece of Islamic architecture built by the sixth Caliph Walid I (674-715) of the Umayyad dynasty like the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus. Its plan also resembles the latter fs, having a broad courtyard and very oblong worship hall put aside to the south (Macca side). The current building is the one reconstructed in the 12th century. Differing from Damascus fs, there are no mosaic decorations in this mosque.

Mosque of Umar I , c.640, 720

In the Roman city of Bosra is one of the earliest mosques, which was built by the Caliph Umar I (r. 634-644) of the Umayyad dynasty, who conquered Syria, and completed by the later Caliph Yazid II (r. 720-724). It is a mosque of simplicity and fortitude and few decorations. Bosra was a resting place for caravans and pilgrims to Macca. Al-Hayr Palace East & West 728/9

There are the remains of two palaces of early Islam in the Syrian desert, to the east and west of Palmyra, called Qasr (Castle) al-Hayr al-Sharqi (East) and al-Hayr al-Gharbi (West). As shown in the plan of al-Sharqi as given below, they followed the form of Roman fortresses with a full-fledged defense system, surrounded by high ramparts with turrets, and embracing a large courtyard. They were built in 728/9 under Caliph Hisham.

(From "The Umayyads" Museum with no Frontiers, 2000) City Walls and Baghdad Gate 8th-10th c.

The city of Raqqa is said to have been founded by Alexander the Great. In Byzantine times it was a front city against the Persian Empire. It fell into Muslim hands in 640 and encircled with city walls in about 772 by the early Abbasid Caliph Mansur. Only a part of the walls and a city gate are left to the present day. Like all the city walls, the Baghdad Gate is also made of bricks, forming double rows of decorative blind arches over the gateway. All arches are not semicircular but pointed, characteristic for Islamic architecture.

KRAK des CHEVALIERS Crusader's Castle, 1170-1250 Crusaders first invaded Syria-Palestine in 1095 and the 8th or last Crusade was in 1270. It was mostly the Romanesque era and early Gothic era in European art and architecture. They established the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem (1099-1291), colonizing many places and constructing castles on mountains and churches in towns. While there remain no Romanesque castles in Europe, there are many in Syria, among which the best preserved one is at Krak des Chevaliers, which literally means the Castle of Knights. In books on the history of European architecture, the photographs of this castle are always put as the best representative of medieval castle architecture.

Cathedral (Notre-Dame de Tortose), 12th-13th c.

The Latin Kingdom created by Crusaders constructed churches, cathedrals, monasteries, and convents in Jerusalem and other places in Syria-Palestine in the style of Romanesque, which was dominant in Europe in those days (later in the Gothic style). ALEPPO Monumental Gateway of the Citadel, 13th c.

The Sunnite Ayyubid dynasty (1169-1250) established by Salah al-Din defeated the Crusaders and recaptured Jerusalem, bringing prosperity to Egypt and Syria. The most famous Islamic fortress confronting the Crusaders was the Citadel of Aleppo. There had been a hill at the center of Aleppo from ancient times, where the Ayyubids constructed a new fortress including a palace, mosques, and urban facilities for the inhabitants, surrounding it with moats at the foot of a steep hillside for defense from the enemy.

Like other madrasas in Aleppo, Zahiriya Madrasa is quite brusquely surrounded with high stone plain walls. The narrow long arched entrance in front is the only accent in its external appearance. Instead of that, the craftsmanship of its stone masonry is so excellent that remindig us Cistercian monasteries in France as in L'abbaye du Thoronet. This is a fine example of 'Asceticism Architecture'. After the restration, its coutyard has regained completely beautiful formality.

Plan (From "Islamic Architecture", R. Hillenbrand, 1994)

This madrasa was donated by Daifa Khatun, the widow of Sultan al-Ghazi, in 1237 on the southern outside of the city wall. For the name of Firdaus (Paradise) Madrasa, there are almost no plants or ornamentation on its external appearance and around its courtyard, likewise in the other madrasas in Aleppo. However, its stone masonry shows an excellent mastery, reminding us of Cistercian monasteries in Europe.

Maristan & Mausoleum of Nur al-Din, 1154, 1172

Strictly speaking, this is not a work of the Ayyubid dynasty but a building complex built by Nur al-Din of the Zangid dynasty (1127-1251), one of the small Atabek dynasties based on the Seljuk dynasty and later absorbed by the Ayyubid dynasty after the death of Saraf al-Din. Nur al-Din was the second monarch of the Zangids, fighting against the Crusaders and dispatched Saraf al-Din to Egypt. The Maristan (Hospital) of Nur al-Din was constructed in 1154 and is now used as a museum of Arabic medical and scientific history.

The city of Damascus was surrounded by city walls since ansient times, having the Citadel on its northwest corner. Its ramparts have many strong towers with machicolations. The best extant is the northeast tower based on a square plan. It is considered to have been constructed in the 13th century. ALEPPO Arghun Bimaristan, 1354

In the world history were there two dynasties of military men of ex-white slaves: The Slave dynasty (1206-90) based on the capital Delhi in India and the Mamluk Sultanate (1250-1571) based on the capital Cairo in Egypt. Mamluk (meaning slave) dynasty defeated Ayyubids and made the high tide of Cairo, ruling from Arabia, including Macca and Medina, to Syria.

In Syria, there are many old public Hammams (bath houses) operated still now. This hammam in Aleppo, also called Hammam Yalbugha, was first erected in built in 1491 in the Mamluk era by the Emir of Aleppo Saif ad-Din Yalbugha al-Naseri. After used as a factory in the 20th century, its devastated building was repaired after 1985 and recovered its original form so as to accept tourists too. DAMASCUS Tekkiye Mosque & Madrasa, 1554, 1566

The Ottoman dynasty controlling the whole of Anatolia took at last Constantinople (now Istanbul) in 1453, destroying the Eastern Roman Empire. It became a great empire, expanding its territory from eastern Europe to Syria, Egypt and Arabia.

Sinan, the greatest Mimar (architect) in the history of Turkey, who had been working for the emperor Suleiman the Magnificent at the dynasty fs apex, also left one of his works in Syria. It is the Tekkiye Mosque in Damascus, also called Suleiman fs Tekke, the madrasa neighboring which in the east was designed by another architect 10 years later, yet in a similar architectural style. A Tekkiye was an ascetic monastery for Sufis, often combined with a poorhouse as here. Bahramiye Mosque, 1583 This is the last large mosque in Aleppo, erected by the governor of Aleppo, Bahram Pasha, in the Turkish style. Like the above Tekkiye Mosque by Sinan, Syrian architecture in the age under Ottoman rule fundamentally took, as a design motif in the outer surface, stripes with white, black and ocher color stones. The interior of the Bahramiye Mosque is akin to Romanesque churches in Europe except its decorative Mihrab.

The prosperous commercial city Aleppo had many caravanserais, which were called eKhans' as in Turkey. Since a khan in a city was the starting point or last stop for caravans, which journeyed a long way between cities transporting commodities, its main purpose was the dealing of goods rather than accommodation. Qaimariye Mosque, 1743

About 150 meters east of the eastern gate of the Umayyad Mosque along the Qaimariye Street is a small but attractive mosque thoroughly covered with three-color (ivory, black and ocher) stripes inside and outside, on walls, arches and even domes. It is the Qaimariye Mosque, the most spectacular example of this characteristic of early-modern Ottoman architecture. It was built in 1743 by Fathi Effendi, an Ottoman treasury official, hence also called the Fathi Mosque.

The Azem Palace is the best piece of Syrian palace architecture. Along with the slightly smaller palace of the same name in Hama, it was constructed by the Ottoman governor of Damascus, Assad Pasha al-Azem. Like the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul, Turkey, it is not to be referred to as magnificent palace but a peaceful ensemble of residence-like buildings and courtyards without a particularly enormous building. It was restored twice in the 1930s and is now open to the public as the Museum of Popular Arts and Tradition.

The most perfectly designed huge khan (caravanserai) in Damascus was constructed by Assad Pasha al-Azem like the above palace, hence the name Khan Assad Pasha.

While khans along highways are lodgings or inns for caravans, those in urban areas are their last stops where they display and trade the commodities that caravans have transported long way.

Traditional Houses (Beits) in Armenian quarter, 17-18th c. In northern Aleppo is a Christian area called the Jdeide Quarter, where Armenians have lived and preserved Syrian traditional courtyard houses (Beits in Arabic) for more than 200 years since the Mamluk Sultanate era. They are mostly mansions, among which the larger ones have been converted to schools and museums. Their well-planted courtyards usually have a fountain or water basin at the center and a two-story high Iwan at one side, which is used as a pleasantly shaded half-outside salon with a tall arch framing the opening.

Visual books that both specialists and amateurs can enjoy

SYRIE : ART, HISTOIRE, ARCHITECTURE 1983, Hermann, Paris, 29cm-260pp. Gerard Degeorge, a French architect, depicts appropriately the history of Syrian art and architecture from Sumerian civilization to the Islamic period with plenty of his own fine color photographs and drawings, which are not so many though. As almost all main architectural works and remains are treated skillfully, this is an ideally suited book to gain an overview of the architectural history of Syria. The text is in French.

The CHRISTIAN ART of BYZANTINE SYRIA Translated from Spanish to English by Eileen Brophy, 1997, Garnet Publishing, 31cm-256pp. Usually Syrian Christian buildings are classified as Byzantine architecture, but buildings treated in this book are all ruins from the early Christian era. In Syria there are almost no examples in the later Greek orthodox style. This large-size book treats only remains of unknown ancient Christian churches and monasteries in various places of Syria with plenty of color photographs. Although the author fs photographing skill is not so great, since there are no other books of the same kind, this book is valuable .

TERRE SAINTE ROMANE Sainte-Marie de la Piere-Qui-Vire, Yonne, 22cm-328pp. This is a book in the collection gLa Nuit des Temps h published by Zodiaque in France, which covers all Romanesque art and architecture in Europe. This special volume treats the Romanesque works (churches, monasteries and castles) by Crusaders in the Terre Sainte (Holy Land) in Syria-Palestine where Christianity was born. This medium-sized book includes a few color photos and numerous black-and-white photographs in fine Gravure printing, which was possible in those days. Text in French.

DAMASCUS translated from French to English by David Radzinowicz, 2004, Flammarion, Paris, 32cm-320pp. Gerard Degeorge , the author of the above book gSyrie: Art, Histoire, Architecture h, has long studied Syrian architecture and has now written a book on the history and architecture of its capital Damascus, almost all of which belongs to Islamic architecture. This is the English edition of this deluxe book full of his own excellent photographs (all in color).

ALEP Gerard Degeorge, 2002, Flammarion, Paris, 32cm-320pp. The companion volume of the previous book gDamascus h is the book on Syria's second largest city Aleppo, i.e. gAlep h in French. This time Gerard Degeorge contributed only photographs, while the author of the French text is Jean-Claude David. An english edition has not yet been published. Like gDamascus h, almost all buildings are Islamic, the photos are all in color, and many drawings are inserted.

MONUMENTS of SYRIA, An Historical Guide University Press, New York, 25cm-320pp. Of all books introduced here, only this one lacks photos. Instead, all important sites are accompanied with drawings or maps. This is an extremely convenient book as an encyclopedia of Syrian architecture, describing minutely every architectural and archeological site in Syria in alphabetical order of the place names. A great work produced by a single author!

(September 02, 2012)  E-mail to: kamiya@t.email.ne.jp

|