|

JANTAR MANTAR in

|

|

JANTAR MANTAR in

|

The intelligent Maharaja of Jaipur, Jai Singh II, being able to understand Sanskrit and Persian, had a passion for science, devoting himself particularly to astronomy and astrology. He collected and studied not only Indian but also Persian and European books on the subjects, and in order to make astronomical observation much more precise, he constructed observation apparatuses, enlarging them up to from the laboratory an architectural scale. Sawai Jai Singh II acceded to the throne, the Maharaja of Amber, at the age of only 13. When he was 20 years old, the sixth Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb died, and the emperorfs sons fought with each other for succession to the throne. Since Jai Singh was on the losing side, his relationship with the Mughal dynasty deteriorated, yet the following emperors changed one after another. He formed a friendship with the 12th Emperor Muhammad Shah (r.1719-48), being appointed the governor of the city of Agra at the age of 33, and the governor of the Malwa region at the age of 35. When he was 41 years old, in 1727, he constructed a new city in the plains, Jaipur, and moved there from mountainous Amber, becoming the Maharaja of Jaipur. In the meanwhile, Jai Singh, who had devoted himself to astronomy, was requested by the Mughal Emperor Muhammad Shah to make accurate astronomical coordinates and a calendar. He first constructed an observatory in Delhi, and then similar ones in Varanasi, Ujjain, Mathura, and lastly the largest one in his own city Jaipur as the synthesis of them. The large observation instruments, called Yantras, were not designed@ in traditional architectural forms, whether Hindu or Islamic, but designed with pure geometry and curves, without any decorations. Since they were based on functions completely different from palaces or temples, when seen as buildings, their forms are amazing and very mysterious with unexpected shapes, reminding us of expressionist architecture in the 20th century or Russian constructivist styles. Besides that, they would bring up in our minds the fantastic works by the evisionary architectsf at the age of the French Revolution, Etienne-Louis Boullée (1728-99) or Claude-Nicolas Ledoux (1736-1806).

The designation eJantar Mantarf is a corruption of Yantra (instrument) plus Mantra (true words, conjuration) in Sanskrit, used for the Delhi Observatory at the beginning. Later it came to also indicate the other observatories established by Jai Singh.

The enactment of the calendar, which would be in common currency anywhere in the state, was an important work of the ruler of government for not only administration but also religious ceremonies, calculation and levy of tax. For the enactment, the accurate measurement of the sun and moonfs movement and their time and fixing the place of the standard point for that were needed. Nevertheless, there had been monarchs in various states since ancient times who were absorbed in astronomy or astrology, some of whom wished to materialize facilities in an architectural scale. While there would have been some realizations in ancient Egyptian culture, it is well known that the ancient Mayan civilization highly developed astronomy, though there is no relation between it and India in this article. There remains a symbolic building from the 10th century, assumed to have been an astronomical observatory, at Chichen Itza, Mexico.

Mayan Observatory at Chichen Itza, Mexico, 10c.

In the Islamic world, huge observation instruments might have been built from old times, in Baghdad, Isfahan, Cairo, Istanbul, and so on. The most famous observatories among them were in Maragheh, Iran, in the 13th century and in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, in the 15th century. Astronomy was much more advanced in the Islamic sphere than in Europe in those days.

Ulugh Beg (1394-1449), the fourth monarch of the Timurid dynasty (r. 1447-49), compiled the eZigef (Ulugh Begfs astronomical table) based on observations through many years at the Samarkand Observatory, which was brought to Europe and eagerly studied. However, after he was assassinated in 1449 by one of his sons during the conflict over the succession to the throne, most of the observation implements were wrecked, and no one took over the work of Ulugh Beg in the Islamic world.

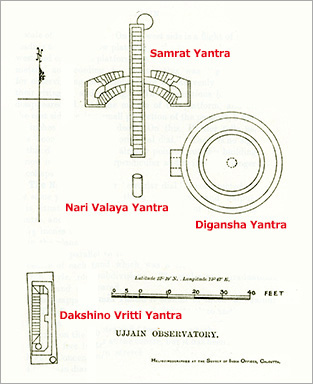

The Ulugh Beg Observatory in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, c.1420 Presently Europe entered the Renaissance, making rapid development in astronomy. In India, it was Sawai Jai Singh, the Hindu maharaja of Jaipur in the 18th century, who constructed a series of collective observatories in several places in India, deeply studying Islamic traditional astronomy as well as new materials brought from Europe. Among classical Hindu literature, there were two Sanskrit treatises on astronomy: gSurya Siddhantah by Varahamihira and gBrahma Siddhantah by Brahmagupta. Jai Singh and his assistant (or more precisely his teacher), Jagannath, finding many mistakes in these treatises, improved observation instruments and enlarged them greatly to get more precise observation values for the true calendar to correctly determine the dates of Hindu festivals. Jagannath wrote a new treatise on astronomy gSamrat Siddhantah in Sanskrit. Jai Singh possibly had shown a small-scale trial observatory to the Mughal emperor Muhammad Shah, who asked Jai Singh to construct a large-scale observatory in Delhi to produce an accurate table of constellations and calendar. Construction began in 1719 and was completed in 1724. Based on the data recorded here, Jai Singh, in collaboration with Jagannath, improved gUlugh Begfs Astronomical Tableh and drew up gZij Muhammad Shahih (Muhammad Shahfs Astronomical Table) to dedicate to the emperor. Subsequently, Jai Singh erected similar observatories also in Varanasi, Ujjain and Mathura, the last of which was unfortunately demolished in the 19th century, leaving nothing behind for us. At the very end, synthesizing all those facilities and experiences, he constructed the great astronomical observatory (Jantar Mantar) of the largest scale at the palace district of his own state, Jaipur.

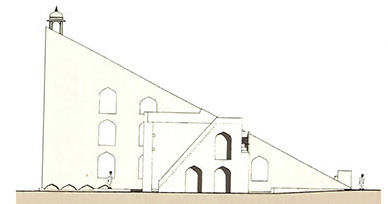

The most important instrument from a practical aspect was a portable eAstrolabef as they were called, which was utilized for various purposes: to observe the celestial sphere, calculate longitude, latitude and time, and refer to the table of constellations. Its origin was in ancient Greece, but it is said to have been put to practical use in around the 9th century in the Middle East. There still exists many of them in Jaipur and the hugest two, made of iron and brass respectively, are suspended from a wooden beam in the Jaipur Observatory, named eYantra Rajf. Their actual use might have been for astrology. What is most architecturally conspicuous in observatories is the enormous eSamrat Yantraf. It is always the highest and largest instrument in each observatory in a shape of a right triangle. The largest one, in Jaipur, reaches 27.5 meters in height, with flight of stairs on its hypotenuse. When going up to the top, one can look out over both the whole precincts and its Yantras (instruments) in one view. Most Yantras in every Jantar Mantar are as large as actual buildings, but they do not use any elements or ornaments of traditional styles of either Hindu temples or Muslim mosques, being thoroughly composed of pure geometric shapes. The great Samrat Yantra in Jaipur is only surmounted with a traditional element, Chhatri, which was used as a watching room for weather forecasts or the advent of monsoon seasons. Only the persons holding those roles could climb, the stairway was controlled with a door at the entrance usually locked. The Brihat Samrat Yantra is a giant equatorial sundial; the hypotenuse of its right triangle casts a shadow on the western arc of the circle in the morning and on the eastern in the afternoon, indicating the exact time on their scales.

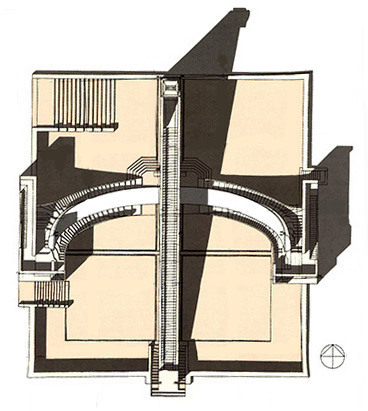

PLAN of the Brihat Samrât Yantra in Jaipur Observatory

In the period when those Jantar Mantars were constructed, as the European astronomy had developed much further, they now do not have such great significance in scientific history from the view point of invention and discovery. However, their sizes of architectural scale and their figures being far apart from usual traditional Indian and Islamic architecture, they rather remind one of Expressionist architects in Modernism such as Erich Mendelsohn (1887-1953) and Bruno Taut (1880-1938), attracting strong attention from contemporary architects. Now we will see the astronomical observatories in India made by Sawai Jai Sing II, one by one.

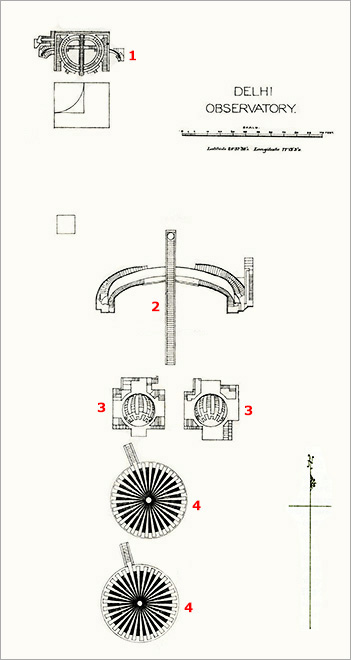

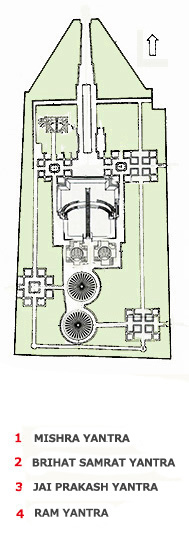

Although Sawai Jai Singh made observation instruments in Delhi following antique documents at the outset, having unsatisfactory results, he is said to have remade all of them in his own design. However, as the most peculiar-shaped attractive Mishra Yantra was constructed after his death, it might have been the work of his son, Madhu Singh. It is also said that Madhu lacked passion for astronomy, so he might have employed a talented architect.

When G.R. Kaye surveyed the Delhi Observatory for the Archeological Survey of India in 1931 at the end of the British rule, it was on a deserted land with almost nothing around it. After the new capital New Delhi was constructed in 1931, the observatory came to be incorporated in it, and has now formed an archeological park surrounded by high-rise buildings.

Brihat Samrat Yantra & Jai Prakash Yantra   Ram Yantra & Jai Prakash Yantra

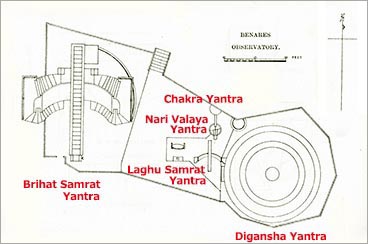

If accepting Kayefs established 1737 theory, this Varanasi Observatory turns out to be the last one, while G. Tillotson insists that this is the third one during almost the same period of 1724-34 as those of Mathura and Ujjain. In short, the construction date of every Jantar Mantar is imprecise.

Ujjain Observatory (Jantar Mantar)

Jai Singh II constructed his fifth observatory in Mathura, on top of Kans Qila Fort that had also been erected by his ancestor, Raja Man Singh at the end of the 16th century. However, the fort was sold off slightly before the Indian Mutiny (1857-8), at the same time, the observatory was dismantled to use as construction materials without leaving any traces. Mathurafs observatory is said to have been built circa 1738, though not confirmed. According to Z.M. Shahi, the order of construction was Jaipur, Mathura, Ujjain, and Varanasi for the purpose of verifying the data recorded at Delhi Observatory, though similarly not a few scholars consider Jaipurfs one to be the second, probably because its inaugural date of construction was early.

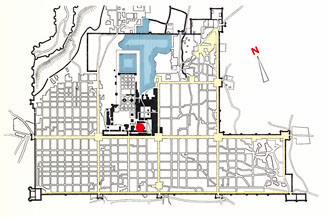

The town consists of nine quarters of 800 meters square each, the center of which is the palace quarter. This orderly city with a grid pattern of roads intersecting at right angles resembles 20th century modernist city-planning. Since most buildings along the main streets are colored in pink, it has a sobriquet of ePink Cityf. It has developed southward nowadays, being full of energy as the state capital. The unique astronomical observatory (Jantar Mantar) of the largest scale was constructed in the palace quarter near palace buildings of Mughal and Indo-Saracenic styles.

In G.R. Kayef book, the Jaipur Jantar Mantar is written to have been built circa 1734, which has been established, while G. Tillotson and others insist that it had been commenced to have been built 10 years earlier than that, about 1718. If so, the shape of its site would not have followed the city-axis of the later city-planning but have naturally followed the north-south axis, so it is more natural to think that the observatory would have commenced to be erected after the construction of the city.

Jai Singh invited a Goan Jesuit, Don Pedro de Syrva Leitao (c.1766-?) who was a man of discernment regarding astronomy, to hear critical opinions and information from Europeans. Pedro came to Jaipur in 1731 and stayed there 60 years till his death. Was it because of his admiration of the Jantar Mantar? Since his colleagues might have joined him in 1740, it might have been pleasant to live under such an intelligent monarch.

As a conclusion, I quote here a part written on Jai Singhfs Jantar Mantars from Henri Stierlinfs gArchitecture de lfIslamh that I have translated once into Japanese for publishing 30 years ago:

For people who would like to know more minutely about Jai Singh's

" THE ASTRONOMICAL OBSERVATORIES OF JAI SINGH"

George Rusby Kaye (1866-1929) researched all of Jai Sing IIfs astronomical observatories and published this book as one of the series of reports of the A.S.I. (Archeological Survey of India) of crown rule in India (Indian Empire). The descriptions are quite detailed with a plan of each observatory and folded map of the city of Ujjain. The copy I gained had been so damaged that the antique bookshop repaired it, rebinding it in half leather.

"A GUIDE TO THE OLD OBSERVATORIES

A convenient book on Jai Singh's Astronomical Observatories (Jantar Mantars) for general readers. It is a reduced and summarized edition of the above-shown book, published two years later by the same author. With plans, drawings and photos (though not many) as well as concisely arranged descriptions, it is a very useful book on this subject for amateurs.

hCOSMIC ARCHITECTURE IN INDIA"

80 years after G.R. Kaye, Andreas Volwahsen deeply studied Jai Singhfs Jantar Mantars and published this book as one of a trilogy on Indian architecture, synthesizing later studies and making new drawings. This is a splendid book full of fine color photographs, which also draw comparisons and describes influential relations with predecessors of astronomies in the globe.

[ͱ¿çÖ kamiya@t.email.ne.jp

|