|

HISTORIC CITY of

|

As was constructed by the Sultan Ahmad Shah I in 1411, the city was designated as Ahmadabad and developed as an Islamic city under the rule of the Ahmad Shahi Dynasty. It also thrived long afterward in the British colonial era through its textile industry, by which it was called Indian Manchester, and in the 20th century became the mecca of modern design in India. Even after the transfer of the state capital to newly constructed Gandhinagar, Ahmadabad is still the largest industrial and commercial city in the state of Gujarat. |

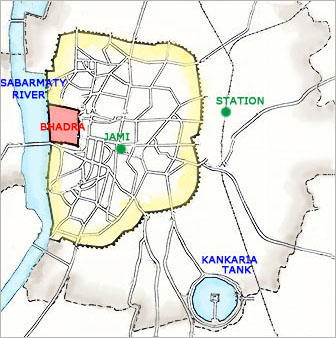

After the first Islamic political power, the Slave Dynasty, came into being in Delhi in the early 13th century, the entire northern India would gradually submit itself to the Delhi Sultanate. In the Gujarat region in western India, when the Hinduist Solanki-Vaghela (Chaulukya) Dynasty, which had been ruling this region until then, collapsed at the end of the 13th century, the Tughlaq Dynasty of Delhi Sultanate got hold of it. The history of Ahmadabad as an Islamic city started in 1411 when the governor-general of Gujarat dispatched from the Tughlaq dynasty, Muzaffar Khan, declared independence from Delhi at the end of the 14th century. His grandson Ahmad Shah I (1389-1442) then constructed his capital Ahmadabad (derived from his own name) on the east side of the Sabarmaty River (-abad is a suffix meaning a city). The name of the dynasty was also called Ahmad Shâhî, derived from the name of the virtual founder Ahmad Shah. In the 170 years since then, architects and craftsmen in this region developed their own characteristic architecture, eGujarat Stylef as it were, leaving a large amount of buildings to the present time. As seen in the above map, the city was encircled with ramparts with many city gates, some of which are extant, and its one side faces a river for its defense and shipping like Delhi or Agra.

The Ahmad Shahi dynasty took over the architectural tradition of Hindus and Jains, especially the technics of their temple buildings that had fully developed under the Solanki dynasty, incorporating them with the principles of Islamic architecture. It created a new architectural style, which united most ingeniously Hindu and Islamic architecture into one, anticipating the later eAkbar-stylef of the Mughal Empire. Conversely, in order to build mosques and other facilities, the local dynasty in Gujarat, which had not brought Persian or Turkish architects and craftsmen, could not help but borrow the helping hand of workersf powerful guilds, which had long been erecting Hindu and Jain temples. The members of the guilds obtained jobs in the new dynasty and well adapted themselves to the construction of Islamic buildings of various functions that were not known so far. Therefore, Islamic buildings in the Gujarat style are continuous from the Jain temples of Mt. Abu and Ranakpur by rigid ties both technically and aesthetically.

Bhadra (Citadel of Ahmadabad) & Tin Darwaza

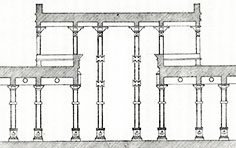

The first building in the new city was the citadel of Bhadra facing the Sabarmaty River, which is now used for the state government, the entrance gate of which is preserved. Since its name is said to derive from a Hindu goddess Bhadra, an incarnation of Kali, it might have been an ancient place name. In the Gujarat region in the 14th century before the construction of the city of Ahmadabad, early Friday Mosques were built in the towns of Bharoch (1322), Cambay (1325) and Dholka (1362), gradually shaping the eGujarat Stylef. The one that established it distinctly was the first mosque of the Ahmad Shahi dynasty, Ahmad Shahfs Mosque in Ahmadabad (1414). Like in the other early Islamized cities, Ahmad Shah dismantled Hindu and Jain temples and reused their components for his first mosque in Ahmadabad. One can easily recognize here many columns and beams elongated by connections of two or three, from which Hindu or Jain images of creatures were scraped off. On the other hand, trabeated stone frames and corbelled domes were by and large from the Indian traditional methods. As for the facade facing the courtyard, a large arch was set at the center, and two minarets were arranged on both sides, as if those parts of the wall swelled up with plenty of carvings, determining the form of later Gujarat mosques.

While Ahmad Shahfs Mosque is located at the southern end of the citadel of Bhadra, the largest mosque, Jami Masjid (Friday Mosque) of Ahmadabad was built at the center of the city 10 years after the former mosque, completed in 1424 by Ahmad Shah too. Fundamentally it was an enlarged version of Ahmad Shahfs Mosque as a hypostyle hall mosque in the Arabic style. The number of columns reaches as many as 364, over which are surmounted 15 small corbelled domes. The minarets on both sides of the central arch are abundantly carved. Muezzins mount the stairs inserted in the thick wall to the roof and then take spiral stairs inside the minaret. However, almost half of the minarets in Ahmadabad collapsed during these 600 years by earthquakes and thunderbolt strikes. The reason is considered that they were too heavy by their ample sculptural fleshing as compared with slender minarets in Turkey and other countries. The lack of upper parts of minarets give the mosques a stocky impression without vertical elements.

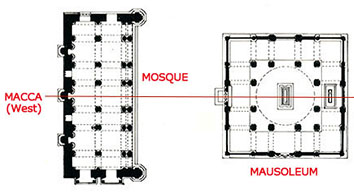

The Friday Mosque of Ahmadabad & its Cloisters When those who are used to seeing Middle Eastern mosques enter a Gujarat style mosque for the first time, they might have a strange impression, for there are no arches inside but tall perpendicular columns and horizontal beams like a jungle gym, repeating endlessly. The courtyard is surrounded with cloisters with dimensions of 63 x 87 meters, looking rather like a square than a courtyard. At the cardinal points of the central fountain basin are four Chabutras (dovecot pillars). Next to the Friday Mosque is the mausoleum of Ahmad Shah built in 1442, the year of his death, probably commenced in his lifetime. Further across the road is the Queen's Mausoleum. The former is a domed building and the latter, in contrast, is an open-air square quarter only enclosed with walls. The cenotaphs there display the dexterity of Gujarat sculptors.

These mosques and mausoleums have a sense of affinity with Jain temples in Mt. Abu and Ranakpur, such as sculptures in their Indian-type domes and stone screens, for they were made by the same Indian traditional sculptors and craftsmen.

Sultan Mahmud Begada, who raised the apogee of the dynasty, erected edifices not only in the city but also in Sarkhej, 10km west of Ahmadabad, a large complex consisting of an artificial lake, a mosque, masusoleums, and a palace building. Further, he constructed a new capital in Champaner. The Friday Mosque of Champaner (1508) can be said to be the magnum opus of Gujarat style mosques, the central dome of which is a true dome.

Muhafiz Khan's Mosque & Mosque complex at Isampur Since Ahmadabad did not become a battlefield, it retains a large number of mosques and mausoleums of the Gujarat style. Most of them are similar, emulating Ahmad Shahfs Mosque and the Friday Mosque. Chief works among them are:

Exterior and interior of Shah Alam's Dargah

At Isampur in the southern suburbs is a nice complex consisting of a mosque and a tomb, and at Vatva 10km south is another mosque and tomb complex, both of which are worth to see. Among many other mosques and mausoleums, a particularly impressive one is the mosque and mausoleum complex built by the Sultanfs queen, Rani Sabrai (the plan below).

As this complex is a 16th century work, it must have developed much higher technics than in the above mentioned 15th century mosques and have acquired Islamic architecturefs structural skills, but this complex used no true arches or true domes. Probably, architects and craftsmen might have been too attached to Indian traditional wooden-like trabeated stone buildings to change their construction methods. This obsession seems to have given special features to Gujaratfs Islamic architecture, dissimilar from other local regional styles, such as Jaunpur, Mandu and Bijapur.

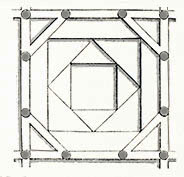

Now we are going to examine Indian corbeled domes a little minutely, which characterized the Gujarat style, starting from eLaternendeckef ceilings as their base. It is also the principle of the domes of Jain temples on Mt. Abu and in Ranakpur, where Indian architecture attained its paramount maturing. Looking at the plan of the complex of Rani Sabraifs mausoleum and mosque, we notice the axes of their column lines completely correspond with each other as mentioned above. They must have been planned and constructed at the same time. The dome of the mausoleum is not supported by walls but peculiarly by twelve columns, betraying the usual Islamic manner.

First of all, columns at four corners are erected of the square circumscribing the domefs circle and they are connected with four beams. If the square is small enough, a stone slab can be put on it as a ceiling or a roof. If the square is large, a triangle stone slab is put on each corner and a larger one on the square surrounded by them. Theoretically, it can be repeated infinitely for a however large ceiling, but it is impossible to be put across a large span with a stone beam that is weak in bending. In those cases, one erects two columns to support each beam, making an octagon with additional four diagonal corner beams, coming closely to the circle of the dome. James Fergusson made it into the schema shown below. Such a system is called in German fLaternendeckef in archaeology, but Fergusson did not use this designation. Laternen decke literally means lantern ceiling because of its three-dimensional formfs resemblance to a Chinese lantern.

A schema of Laternendecke by J. Fergusson Although there are diverse opinions as to whether it originated in stone construction or wooden, it would be more natural to suppose both used to be done side by side. The inner side triangular pattern of the schema is well displayed in the stone ceiling of Parshvanatha Temple at Bhatkal, India, though comparatively new as it was built in the 17th century. On the other hand, the oldest example of the outer side octagonal framed ceiling pattern with stone beams is seen in Turkey. It is the Mausoleum of a family of Gümüshkesen (or Gümüsh teken, meaning silver purse or box) in Milas (ancient Mylasa), which is said, though uncertainly, to have imitated on a smaller scale the renowned Mausoleion (the tomb of Mausoleus, nonexistent now) in Bodrum (ancient Halikarnassos). It is a contemporary work of the Pantheon in the time of ancient Rome, in the second century. In spite of the fact that the builders in that age surely had the skill to build true domes, they stacked here diagonal beams (angle braces) to make a Laternendecke ceiling. The number of its columns is twelve like the schema, seeming to indicate the wooden origin. The adherence to the trabeate structure, disregarding the knowledge of the true dome, might suggest that such a trabeate construction system was general in the regions from Anatolia to Caucasus, and accordingly I suppose that these regions might have been the home of the Laternendecke ceiling method.

Laternendecke ceilings at Bhatkal and Gümüshkeshen The oldest Laternendecke in India is the wooden ceiling of the Lakshana Devi Temple at Barmaur, which is assumed to have been erected about 700. It is an Indian version of the stone ceiling of the Gümüshkesen, probably brought from Caucasus via Central Asia. As it is on a smaller scale, its columns are only four. A typical stone version in India is the Hindu temple at Pandrethan in the suburbs of Shrinagar, Kashmir, two centuries later than that of Bharmaur, not necessarily indicating its wooden origin, for in the past numerous similar temples must have been constructed of both wood and stone.

Wooden ceiling in Bharmaur & stone ceiling in Pandrethan On the other hand, in Caucasus in the west, another method of making quasi domes by corbeling upper triangular small plate from circumference orderly was performed, forming an angular lantern shape ceiling, as if being the source of its name eLaternendeckef. It was largely done from wooden folk houses to stone churches. In Armenia it was called eHazarashenf, a stone ceiling of which is extant in only one place, Getashen.

Many researchers insist that this system is the origin of Armenian stone domes, but I do not utterly think so. It is clearly understood that the corbeling structure never does develop into a true dome, if observing the history of Indian architecture. There is actually an interminable distance between corbeling stones horizontally and piling them radially, even though it looks like only one step. In a region where wood is plentiful, the force to invent true arches and domes does not work.

This system was transmitted from Central Asia to even as far as China. Among Islamic architecture (Qingzhen Si) that I searched for China, there are many Laternendecke ceilings (how suitable for China!) in Botou and other places.

wooden ceilings in Botou & Erzurum Indian domes look to have most faithfully followed the form of Gümüshkesen in Turkey. It puts beams octagonally over twelve columns on a square, then narrows it into a sixteen-agonal shape, almost a circle, from which it corbels smaller circles one by one in regular sequence, making almost a complete dome. This is the method of Indian stone domes. Since it is not possible to corbel steeply, its total shape does not become perfectly hemispherical but a little conical, and the maximum of their diameters is about eight meters, whereas a true dome with radially piled stones can span as large as thirty meters.

Indian dome in Ahmadabad & Somnatha-Pattan Supporting domes not by walls but by wooden-like post-and-beam frames was Indiafs monopoly, scarcely seen in the west. Furthermore, by sculpting the underside of the domes minutely, the Indian style dome was completed. It was Jain craftsmen who advanced this style greatly, attaining its peaks at Mt. Abu and Ranakpur. Since Ahmadabadfs Islamic architecture succeeded to these techniques, the Mausoleum of Rani Sabrai and the Friday Mosque of Ahmadabad have corbelled domes over twelve columns. That is, they are Laternendecke ceilings.

Free standing canopies on Makli Hill and in Kiradu

Adding one more thing, in a corbelled dome scarcely works the thrust, which is the stress to force arches and vaults to open and collapse, for the stress of corbelled domes is almost only vertical, making possible independent canopies standing over post-and -beam frames without walls. In whatever religion, free standing canopies are often seen in Indiafs cemeteries as roofs for tombs, which would look strange for architects from the Middle East. Each Gujarat style mosque fundamentally has two minarets adhering the walls both sides of the central entrance arch to the worship hall. They obtrude high in the sky, effectively contrasting to the wide horizontal facade of the worship hall. However, the upper parts of almost half of them have collapsed in earthquakes or due to thunderbolts, the rest of which show clearly the Gujarat-style minaret with fleshy sculptures, definitely contrasting with the slender, smooth Turkish-style minaret. What is still more interesting in Ahmadabad is the eShaking minaretsf as they are called. When one of a pair of minarets is shook little by little by pushing with all onefs strength on the roof, the other begins to shake by itself, probably because their foundations are firmly bound together underground. There are many couples of such minarets in Ahmadabad, suggesting that those of the Friday Mosque would have been the same. This was often called one of the eseven wonders in the worldf.

The best-preserved pair of shaking minarets is that of the Sidi Bashirfs Mosque, which was built by Malik Sarang, a high-ranking official of Mahmud Begada, but its worship hall has been lost now. The free-standing minarets themselves show off their splendid appearance at the height of 21.3 meters.

Bibi-ki Mosque's Shaking Minarets

Another notable item is the step well that was taken over from those of the Hindu period. The oldest one in the city area is Mata Bhavanifs Step Well, the first construction of which goes back to the 11th century and is now used as an underground Hindu temple. This step well is 6 meters in width, 70 meters in length, and 20 meters in depth, providing a long continuing grilled frame of columns and beams, over the long flight of steps, to oppose structurally against the earth pressure of both sides. The inner perspective view of its frame, all carved exquisitely like a temple or palace, is fantastic, but it has no carvings of creatures, being an Islamic building. In front of the innermost well shaft is a square hall with a water basin, where people could take a cool rest. The upper parts of here are most amply decorated, and the spiral stairs on both sides function as a shortcut to the ground level.

Dada Harir's Step-well

In the southeast of the city area was made a large Talao (artificial pond or lake) by Qutub-al-Din Ahmad Shah (r. 1451-58), drawing water from the Sabarmati River, in the middle of the 15th century. This circular (actually 34-angled shape) Kankariya Tank is one of the largest Talaos in India, encircled with stone stairs like a Ghat facing a river or a lake, the length of which amount to as long as 1.4 kilometers.

The most noteworthy craftwork is the stone Jâlî (window lattice screen) of the Sidi Sayydfs Mosque (1572). The two large semicircular windows are fixed with elaborately carved Jali with the motif of trees spreading branches, the designs of which are superexcellent without equals. It consists of 17 continuous stone panels on the base of 2.9 meters, shading from sunlight and letting wind flow through during hot days.

A window screen and a Mihrab of a mosque Including flat compositions of Jali in windows, Gujarat stone carvings established the obvious eGujarat Stylef as a half three-dimensional architectural ornamentation, even if there are no sculptures in round. Aforementioned mosque walls, cenotaphs of mausoleums, and brackets of minarets, as well as column capitals and bases and podium carvings are all delicate but not excessive, bringing about balmy and agreeable formation. Above all, the Gujarat-style Mihrab is very attractive, making its inside as a shallow small room with an arch in the foreground and a disk and a pot carved on the back wall, then on the top is Torana decoration borrowed from Hindu or Jain temples. These are the fructification of the endeavors of the sculptorsf guild, which had continued since the Solanki dynasty before the advent of Islam, to adapt their traditional technics and aesthetics to Islamic buildings.

A stone column base and a wall sculpture

The city of Ahmadabad, which has never been a battlefield, retains the old city, at least its structure, houses and urban facilities to considerable degree. Roughly speaking, the old city was an assemblage of Pols. Primarily, a traditional housing block around a main street was a Pur, and the central street was a Pol, but gradually those blocks came to be called Pols. Ahmadabad is said to have 356 Pols.

A gate of a Pol and a preserved house

In western India, traditional mansions are called eHavelisf. Stone Havelis are seen in many cities in the state of Rajasthan like the famous Patwon-ki-Haveli in Jaisalmer. In Gujarat State, there have been left wooden Havelis, though not so many. Wooden temples made in the same style as Havelis are sometimes called eHaveli Mandirs (Haveli temples)f. Originally, the Haveli does not concern with whether it is stone-made or wooden. Ahmadabadfs Pols also retain numerous wooden town houses, though not so gorgeous as Havelis, having carved minutely their columns, brackets and street-facing windows. Most of them have a Chauk (courtyard) for lighting and ventilation, also using it as a salon or parlor. These wooden houses are being lost year to year, whereas the action of preservation is executed in minor scale.

Wooden houses in Ahmadabad Pols When walking in Pols, one often comes across small independent column-towers made of wood or stone. If knowing south Indian Jain temples, he or she would recall eMana stambhaf or eBrahma stambhaf standing in front of temples in southern India, but Ahmadabadfs column-towers are not as high as them, easily ascended by a ladder to their top spaces. They are Jain Chabutra (or Chabutro, Chabutaro), meaning dovecot or a bird feeder. As it derived from the Gujarati word eKabutraf meaning pigeon, it is also called ePigeon towerf in English.

Jain Dovecots and Mana Stambha

However, people do not eat these pigeons unlike those of Egyptian pigeon houses. There are more Jains in western India than in other areas. Jains are known as followers of Jainism making it a principle not to be violent to or kill any animals, vegetation, fishes, birds, or even small insects. They operate a birdfs hospital in Delhi, where wounded birds are cured and hospitalized free of expense. Although Ahmadabad was constructed as an Islamic city, Jains and Hindus lived together with Muslims, maintaining their temples at many places in the city. In the 18th century when the rule of Mughals was weakened, there occurred Solanki-style revival, where Jain and Hindu temples were constructed in the past traditional styles. Gujarat style Islamic architecture was based on western Indian traditional styles by nature, so there would not have been much sense of discomfort.

The largest temple modeled on the Jain temples of Mt. Abu is that donated by Sheth Hathisingh, a wealthy Jain merchant. It was dedicated to the 15th Tirthankara Dharmanatha, one of the 24 Tirthankaras (Jinas or victors) of Jainism in the distant (legendary) past. It was built in the traditional method of stone architecture, reviving the medieval Solanki style as faithfully as possible, though here is also the influence of Islamic architecture such as multi-lobed arches.   Sheth Hathisingh's Temple and its Stambha In recent years, a new eStambhaf (monumental pillar) was erected in its precincts, modeled on the Kirti Stambha (Tower of Fame) in Chitorgarh, but its degree of perfection cannot compare with the latter. Hindus seem to have preferred to build wooden Haveli mandirs than Solanki-style stone temples. Its best representative ones are the Dwarkanath Temple and Swaminarayan Temple. In the precincts of the latter, a huge wooden continuous edifice of four (partly five) stories encircling the vast courtyard is much more majestic than its main shrine. The capitals and brackets of wooden columns are delicately carved, and in its recent restoration the edifice was wholly painted colorfully. Not knowing if originally built as an Ashram (seminary or monastery), numerous private rooms are lined on each floor, used now as dwellings, offices, and even stores, needless to say facilities for the temple. At everyday worship time of the deity, devotees crowd around the main independent shrine. On the festive days, the vast courtyard is filled with a great crowd of followers.

Dwarkanath Temple & Swaminarayan Temple Among architecture merging India and Islam, the Akbar style made by Akbar the Great reflected his will to unify Hindus and Muslims for the upkeep of the Mughal Empire in architecture, while the Gujarat style is thought to have been made by the power of the guild of architects and craftsmen, who had highly developed Solanki architecture for Jain temples, rather than under dominatorsf will or policy. Although Islam conquered the Gujarat region on political and military fields, it was not able to sweep away existing systems of architecture and had to resort to the traditional technics and aesthetics of the local practical architects and craftsmen, except to make no statues, unlike Hindu and Jain temples. (March 01, 2018) E-mail to: kamiya@t.email.ne.jp

|