|

SOMAPURA MAHAVIHARA at

|

|

SOMAPURA MAHAVIHARA at

|

While Buddhism was disappearing in India in the 13th century, its last flourishing region was Bengal, which was composed of current Bangladesh and West Bengal in India. The Vicramashila Mahavihara in Antichak, West Bengal, probably the largest monastery, was demolished, while the Somapura Mahavihara in Paharpur, Bangladesh, constructed by King Dharmapala, is in a relatively well-preserved state as historical remains.

The Stupa, monk cells, and all other buildings were made of brick and their main surfaces were embellished with carved terra-cotta panels. Like in Persia, where Islamic buildings were built of brick due to lack of good quality stone, instead developed colored overglazed tile for their wall finish. Bengalese used for that purpose terra-cotta panels that had been quickly carved on the surface before the dry-up of clay, also due to lack of good stone. Later, this technique would be taken over by medieval Islamic architecture and early modern Hindu temples in Bengal.

|

|

Visiting the ruins of Paharpur early in the morning, one can see the pyramidal silhouette of the Great Stupa gradually emerging in the morning haze of the rural landscape. When the daybreak sun begins to shine on the vast Vihara (monastery), the Great Stupa, which has been soaring since more than 1,000 years ago, appears distinctly in the center. The Somapura Mahavihara boasts the largest scale in the south of the Himalayas and was the most important cultural center in Bengal, drawing a multitude of pilgrims.

Recently many bronze statues of Buddha were excavated from this site and more than 60 stone sculptures are still in the niches of the Great Stupa fs walls, which were buried in the earth for a long time. The Bengal, now divided into Bangladesh and West Bengal in India, was historically and culturally united as one region. It was an outlying district in ancient times, dependent on the central Mauryan or Gupta dynasties. It was the Pala dynasty that established an independent monarchy in Bengal in the 8th century, ruling over this area until the 12th century. In particular, the 2nd king Dharmapala (r. 770- c.810), extending his power over the Bihar region, not only controlled the whole of Eastern India, but also erected many temples and monasteries, protecting Buddhism. Although most of those Buddhist facilities have disappeared, the two representative mahaviharas (great monasteries) were this Paharpur one on the Bangladesh side and the ruined one on the Indian side, the Vicramashila Mahavihara.

Monasteries are called Viharas in India, literally meaning ea place to spend time f, and an inscription found here taught us the name of this monastery as Somapura Mahavihara. Excavation started in 1923 and its detailed report was published in 1938 (A.S.I. Report, No.55 gExcavation at Paharpur h).

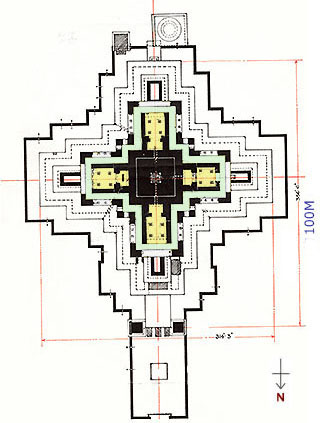

The three-storied Great Shrine takes the form of a Chaturmukha (four-faced) temple, which, in the past, would have had four large statues of Buddha on the cardinal points back to back, each facing outward. However, since its top story collapsed, and the next story fs surfaces have also been lost, its original features cannot be pictured.

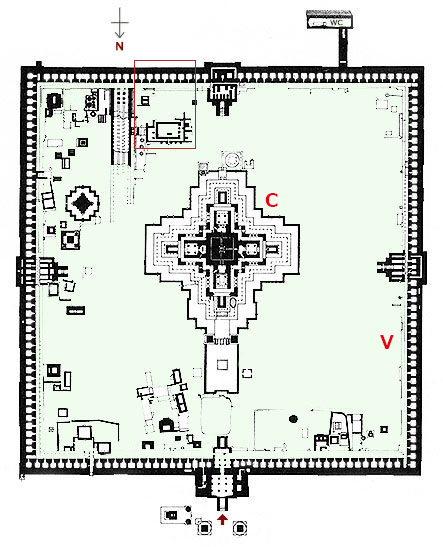

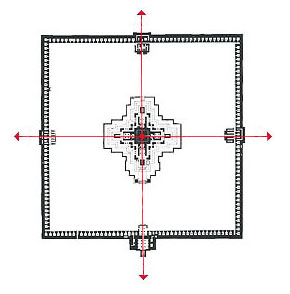

The plan of the Somapura Mahavihara is square enclosed with thick brick walls along with a line of monk cells, having a gate at the center of each side. The largest is the northern one, which was the main gate. In the vast precincts were scattered many small shrines, a dining hall, a kitchen, and other buildings. The Great Chaturmukha (four-faced) Shrine held a large niche for a Buddha statue on each side, which faces each gate, and stands on a double podium, which also functioned as ambulatories, or corridors encircling an object for worship to walk around clockwise. This great shrine can be considered as the developed form of a stupa, a kind of a tomb of Buddha in the shape of a dome-like mound. In the Gandhara region in the west (now in Pakistan) a stupa area and a vihara were separately erected, forming a temple together. Here they were unified in the form of a great stupa surrounded by monk cells in a vast square shape. As a result, the temple form with a large geometric Mandala-type plan spreading to the four quarters, was established here and was then transmitted to Southeast Asia. It was furthermore scaled up from at the temples in Pagan, Myanmar, until the Borobudur, Indonesia, through the Angkor-Wat, Cambodia, under the influence of Paharpur. I have already written that this form was originated in Jaina temples, in Chapter 6 of gJaina Architecture in India h on this website, gThe Adinatha Temple at Ranakpur h.

Buddhism, which was destined to die in the Indian Subcontinent, still flourished through these construction activities of temples and monasteries in its last stage by the kings of Pala dynasty. Terra-cotta panels embellishing the Great Stupa express the vivid popular culture of this region, depicting peasants, musicians and dancers, as well as animals, plants and even demons. The Pala dynasty declined and eventually to die in the middle of the 12th century, keeping in step with Buddhism disappearing from India. After the replacement of the Pala dynasty by the Hinduist Sena dynasty, this monumental building in Paharpur constantly drew pilgrims, but the monastery was not preserved in a good state, leaving it to be pillaged and completely devastated. The reason for the eastern half of this Bengal region later becaming an Islamic country, Bangaladesh, seems to be that Buddhists became Muslims after their defeat in the conflict of hegemony with Hindus. For in the case that Buddhists were absorbed into Hinduism, they would have been ranked in the lowest caste, and so they might have chosen the egalitarianism of Islam to avoid it. (In "UNESCO World Heritage" vol. 5. 1997, Kodan-sha )

E-mail to: kamiya@t.email.ne.jp

|