|

LYCIAN INFLUENCE

|

|

LYCIAN INFLUENCE

|

When talking about cave temples, one will naturally recall those of India such as Ajanta and Ellora. The technique of creating cave temples was introduced to China (Tun-huang, Yun-kang and others) along with Buddhism. Compared with Indian cave temples, Chinese ones have many more wall and ceiling paintings, though they lack many characteristics from the architectural point of view. In Pakistan, cave temples are few, but in Afghanistan, we can find interesting western style carved ceilings in domes and laternendeckes at Bamiyan etc. The cave temples in India have no superior in the world in their magnificent carvings and architectural formality, with pillars and beams in systematic order. In contrast to the fact that wooden buildings of ancient times were almost completely lost, about 1,200 ancient cave temples still exist, mainly in the Deccan, because they are carved structures on the strong rocky mountains. Approximately 75 percent of them are Buddhist, and it has been widely considered that they inform us about the figure and construction system in ancient times as replicas of the then current freestanding wooden temples and monasteries.

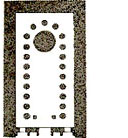

A Hindu temple is fundamentally a 'house of a god', but the Buddhist caves are combinations of 'Vihara' caves, where priests lived, and 'Chaitya' caves, chapels enshrining a 'Stupa'. Those conbination caves follow the same manner of the monasteries and Chaitya halls built of wood or brick on the ground. We can see the plans of such wooden temples through excavated foundations in various sites, but it is not clear what the appearances of their upper structures were. The ancient wooden architecture in India was consequently to be analogized from the figures of cave temples.

When I wrote the books "The Guide to the Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent" and "Architecture in India", there was nothing for it but to summarize such a common view in related chapters. Although it is no problem to think that a Vihara cave is a replica of a single-story wooden building with a flat roof, except for the thickness of its elements, for a long time I was rather doubtful of the view that regarded Chaitya caves to be precise immitations of wooden structures.

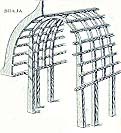

On the other hand, it is not easy to build a curved roof like a barrel vault (i.e. semi cylindrical ceiling) with the use of wooden material. How on earth could they make semicircular rafters as seen in cave temples? It was impossible to bend large pieces of timber with ancient technology. The art historian E.B. Havell insisted that the Indian arch was made of bamboo. However, bamboo is also an extremely solid material with a pipe structure with flanges, which is difficult to bend. Apart from slender bamboo used for craft works, builders could not bend large pieces of bamboo such as to be used as the building's framework. Even if relatively slender bamboo is used, one should tie up the bent bamboo by a tension member to keep the arch form. However, the arched rafters in Chaitya caves are placed freely above the pillars without any suggestion of a tension member. After careful consideration, I reached the following conclusion; the interior spaces with barrel vault ceilings at Chaitya caves were created as only an interior design, with no connection to the fundamental structure of the whole building. The building itself would have been a box type with a flat or gabled roof. Inside of the building, they must have hung a cylindrical ceiling with wooden archd rafters, made by pieces of board linked by 'butt joints' as an interior design. Such a ceiling matches the hemispherical form of stupa, and as we see in the Chaitya cave at Karli, ancient architects created such a splendid interior space, in harmony with the gentle curve of the stupa.

The next question is how they got such an extraordinary idea as to compose a cylindrical ceiling by setting arched rafters in a row in the building. It is unlikely that they designed such a form without any model. A more curious point is in the design of the 'Chaitya window' on the facade. It consists of a large 'Chaitya arch', and is also carved as if it were a wooden structure; purlins on the rafters are supporting a cylindrical roof. Besides, the whole facade is designed as a sort of pointed arch with a horn on top.

There are caves and sarcophagi with pointed arches in Lycia, moreover carved as if they were wooden structures. Many of them were made in the 4th century B.C.E. As to India, the first cave temples appeared in the middle of the 3rd century B.C.E. They are the caves at Barabar and Nagarjuni Hills built for Ajivikas by King Ashoka.

According to the "Anabasis (The Campaigns of Alexander the Great)" by Flavius Arrianus, the Lycians surrendered without fighting and accepted being put under the control of Alexander's army. Consequently, nothing was destroyed in Lycia. The book also says a Lycian interpreter-commander accompanied Alexander the Great as far as the Gandhara region in India (present day Pakistan), taking command of the army. It is not difficult to consider that Lycian architecture was introduced to India together with Greek culture at that time, or after the coming of the Seleukos Dynasty and the Greek Baktria Kingdom.

I set up the hypothesis mentioned above based on books on Lycian archaeology, and presented it at the Summer Seminar of 'The Indian Archaeology Society' in summer 2000, and also at 'The World Archeology Excavation Academy' in autumn of the same year.

Recently, Turkey has become a very comfortable country for tourists compared with my first visit of twenty years ago, with convenient transport, comfortable accommodation, delicious and cheap meals, etc. Besides, Turkish people are generally kind and amicable. As modernization is proceeding also in India since it adopted an open economy policy, a similar comfortable journey might also be expected there in the near future.

Lydia reigned the southwest region of Anatolia in the 8th - 6th centuries B.C.E., fighting with Phrygia of the central region. Nevertheless, it was conquered by Persia in 546 B.C.E. and lost her capital Sardis, and later became a Roman territory.

I asked the staff at the Artemis Temple about the location of the Lydian era Necropolis and went up the hill looking for the vestiges, but unfortunately I could not find any. As far as the information of the excavation report of Sardis, which I gained at the superintendent's office of the Gymnasium, it seemed that there were rather few physical remains to see in this site.

Leaving Sart, I visited the famous Roman site, Ephesus, and then headed to the Lycian sites. However, I will describe the Phrygian ruins first according to the historical order, though I visited them later.

At first, I visited Midas Şehri where there was a large town on the hill in ancient times. So it is called Midas Town. Now the remains are only a cult throne, tombs and a deep cistern, but a huge rock-cut tomb stands at the foot of the hill. This is the famous Midas Tomb. (The name of King Midas who is famous for the episode of 'King's ears are donkey's ears' was likely popular at the time and also in Gordion we can see an old mound called the Tomb of Midas.) The Tomb at Midas Şehri is a rock-cut tomb which is 17 meters high, and has a carved temple facade with a gabled roof. A niche excavated on the lower part is probably for the Goddess Cybele, and the frontispiece is wholly chiseled into geometric patterns. It looks like later Islamic architecture or Modern design. As the general motifs of ancient carvings are animals or plants, it is surprising to find plenty of abstract design on rock surfaces around Midas Şehri. It might have some relationship with the oldest style of Greek art, the so-called 'Geometric Style'.

Going south from Midas Town, I looked around many Phrigian remains such as at Bakshish and Yapuldak. It was very difficult to find them because they are not popular subjects for sight-seeing, small in scale, seriously weathered by the passage of 2800 years, and besides they are inconspicuously scattered around remote places away from the villages.

Phrygian Cave Tombs, Bakshish and Yapuldak

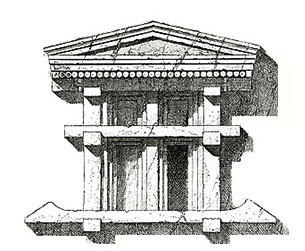

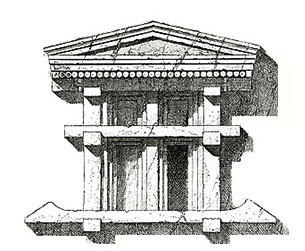

I found that they were basically carved in the shape of houses with a triangular gabled roof, such as the Midas Tomb, or in its developed form, the temple-type. In the 8th century B.C.E. temples in Greece were still built of wood. It seems that in Phrygia too similar wooden temples like these rock-cut tombs might have been built. In Aslantas nearby, the figure sculptures of two lions facing each other are carved on the rock, just like the 'Lion Gate' in Mykenai, showing us the link of civilizations. In Phrygia since then, the lion motif appears frequently, mainly on pediments.

The two largest festivals of Islam, 'Eid', are referred to as 'Bayram' in Turkish. The festival that marks the end of Ramadan (the period of fasting) is called 'Şeker Bayram', and the festival of sacrifice held in the pilgrimage month is called 'Kurban Bayram'. The latter festival coincided with my stay in Turkey this year (2000), falling on March 15-18. During the festival, government offices and companies are all closed, and people living in cities go back to their hometowns, just like Japanese people during the 'Bon' festival. Long-distance buses, the main Turkish transport, and hotels were all full, and on the 16th, historic sites were also unfortunately closed.

Thanks to that, I missed the Crusader castle in Bodrum, and I could only enter the Mausoleion of Halikarnassos. However the famous mausoleum of Mausolos, a satrap of Caria, was no more than a heap of rubble, which did not properly allow me to imagine the ancient majestic figure.

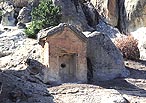

The tombs are carved on the precipitous cliff, possibly ensuring nobody enters, so it is better called 'cliff-cut tombs' rather than 'rock-cave tombs'. They must have been carved by people using rope from the top of the cliff.

There are many temple-type cave tombs in Lycia, and the best-preserved are in Fethiye, which was called Telmessos in ancient times. The town was destroyed by an earthquake, and has been restored as a new port town. In the craggy mountains behind the town, many rock-cut tombs remain. Mainly they are of house-type rock-cut tombs, with some large temple-type tombs.

On the house-type tombs, the facade is carved as if wooden logs are set out as the roof, whereas in the temple-type tombs, square joists are carved, not along the rafter of the roof, but on the horizontal girder. Such a style is common with Greek temples, different from the pointed arch-type rock-cut tombs or sarcophagi in Lycia. What would be the reason for such a difference, I wonder? I was overtaken by a bad thunderstorm in Fethiye, but the next day was very fine, and I hired a car to visit various Lycian remains. At first I enjoyed various forms of remains at Tlos under the shining morning sun, such as ruins of the castle, cave tombs, sarcophagi, a Roman theater and a bath. And then I visited the remains of Pinara, which are spread over a vast area, Xanthos, once the ancient capital of Lycia, remains around the sunken city of Kekova in the sea, the flourishing port town of Antiphellos, now called Kas, etc. These Lycian cities which have existed since the 4th century B.C.E. are scattered along the beautiful coastline of the Mediterranean Sea.

(From "Xanthus, Travels of Discovery in Turkey" by Enid Slatter)

It was Charles Fellows (1799-1860), the English archaeologist, who first thoroughly investigated the ancient Lycian cultural remains. His first exploration of Lycia was in 1838, after which he wrote "A Journal Written During an Excursion in Asia Minor". His second exploration in 1840 was written up "An Account of Discoveries in Lycia". These two books attracted considerable attention from English artists, art historians and archaeologists.

In the 19th century, European archaeologists and architectural historians launched themselves on investigations to Asia. Stimulated by the information from preceding travelers and explorers, Fellows started traveling to research Anatolian culture, and discovered previously unknown Lycian remains. He made efforts particularly to research the remains at Xanthos, the ancient capital of Lycia. Based on his report and his advice, the British Museum carried many Lycian remains to London including the most important 'Nereid Monument' and 'Tomb of Payava' with the assistance of the Royal Navy.

In 1848, over 150 years ago, the 'Lycian Room' was opened in the British Museum and its display became very popular. However, in the 20th century Lycian art and the name of Fellows gradually came to be forgotten, and the items in the Lycian room were scattered. Since then, there has been rather little development in the study of Lycian archaeology.

The Necropolis at Myra

Although called the 'Lycian Kingdom', its actual form in the 4th century B.C.E. seems to have been a union of city-states, named the 'Lycian League'. According to Plinius, the league at the time consisted of thirty-six cities, the largest of which was Xanthos. As the Lycians were fiercely independent, their region was the last in Anatolia to be placed under the command of the Roman Empire.

The tombs are basically assorted into two categories; cave tombs and sarcophagi. The former are further divided into three types. The first is the 'temple-type' that is most monumental (already mentioned in the previous chapter), and not particularly limited to Lycia only. It is the same type as the wooden or stone temples with triangular gabled roofs in Ionia or Greece, though in those cases, they are not cave temples.

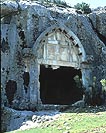

The ruins of Myra are located 2km from the town of Demre where the Byzantine church of Saint Nicholas (who is regarded as the origin of Santa Claus) remains. The tens of rock-cut tombs are piled up in the hill behind a well-preserved Roman theater, and the view is so impressive. Their figures are the reproduction of wooden houses, and their pillars and beams are carved as if put together by wooden 'halving joints'.

It was interesting to find a reproduced wooden house that might have been the archetype of the house-type tombs. It was built at Limyra and actually inhabited. They closely follow the original, but its decorative warped groundsills and beams are made with jointed wooden pieces, which prove the difficulty of warping timber as expressed in the tombs. Perhaps, only for the rock-cave tombs, they might have been carved with exaggeration.

House-type cave tomb called 'Painted Tomb', Myra On the hill behind Myra, there are house-type tombs with many splendid relief carvings. 160 years ago, when Charles Fellows visited there, there were partial remains of vivid coloring, and he named it the 'Painted Tomb'. Although the lower part of the central pillar of the facade has been demolished, a framework of wooden-like 'post and beam' structure remains in good order. The pillars are not flush with the beams in combining together, seeming to represent a real wooden structure.

These house-type tombs are equivalent to the Indian Buddhist vihara caves where priests lived. The facades of the vihara caves are in different proportion from the Lycian, as thick as a stone structure, but their interiors are the perfect replica of a flat-roof-type wooden building, with large beams between pillars, small beams joining them, and smaller purlins lying on top of them. It shows the same principle as Lycian wooden architecture.

Ancient people made coffins for the dead either of wood or stone, and sometimes stone coffins to put wooden ones in. In any region where the Roman Empire dominated, sarcophagi in the form of gabled houses, often decorated with splendid reliefs, were used as memorials for nobles.

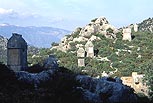

However, the Lycians, solely, developed a unique form of sarcophagi. Of the several hundreds of stone sarcophagi that remain in Lycia, some are simple and some are gorgeously carved. The form of their lids, however, are exclusively of the tall pointed-arched roofs, not the shallow gabled roof-type.

Sarcophagi on the hill of Simena and Istanbul Archaeological Museum On the roof of a sarcophagus, there are six cubic prominences; one each on the pediments and two each on the lateral sides. The sarcophagi for higher class people have lion heads carved on each prominence. The fact that they are limited to figures of lions seems to indicate a continuous tradition from Phrygia. A good example is found in a grassy plain at Sura near Demre, but its box part has no ornamentation. The most decorative sarcophagus was discovered at Sidon in Lebanon, together with the famous 'Alexander Sarcophagus' in the Ionic style. At present, it is displayed at the Archaeological Museum in the precincts of Topkapi Saray, Istanbul. Its gable sides have carvings of winged angels and centaurs, and the lateral sides have lion heads and equestrian cavaliers. On both ends of the ridge, a palmette stands like a Japanese 'Oni-gawara'. In the case of the sarcophagus at Sura, a ridgepole lies at the top, which is the basic type of a Lycian sarcophagus. Checking the gable face (tympanum) carefully, one realizes vertical and horizontal lines carved around the lion head. These lines indicate small posts and beams. In addition, rafter lines are also carved along the curve of the roof edge. In short, Lycian sarcophagi were sculpted as if they were wooden buildings, just as the cave tombs.

Upper part of a Lycian sarcophagus in Kas and Tomb of Payava

A sarcophagus preserved in the town of Kas shows this fact more clearly. It soars in the middle of a road on a high pedestal, on which inscriptions are engraved with Lycian letters.

Why only in Lycia were such pointed arch-type sarcophagi made, despite the fact that the triangular gabled roof was the ordinary design? It is difficult to assert the reason exactly, but we can trace the changes of their forms.

The history of Lycia is almost clear as the ancient epigraphs are deciphered owing to the inscriptions on monuments written together in three languages, Greek, Lycian and Aramaic. According to the inscriptions, the majority of cave tombs and sarcophagi in Lycia were made in the 4th century B.C.E. It is quite probable these forms and techniques were brought to India after the eastern expedition of Alexander the Great late in that century, and influenced the Lomas Rishi Cave at Barabar Hill that is the first cave temple with an ornamented facade in India.

Though there remains no inscription on the Lomas Rishi cave, the plan and interior space suggest that King Ashoka had it made in the middle of the 3rd century B.C.E. together with the adjacent Sudama cave that has an inscription by Ashoka. The technique of excavating rock caves itself might have been brought from Persia to India, not from Lycia.

This facade has been regarded as an accurate replica of wooden architecture at that time. However this is impossible, as it is too strange to be a wooden building form. As already stated, it is irrational from the structural point of view; its fundamental attitude is forcible manipulation to make the gable shape a 'pointed arch' by the improbable bending of rafters, which should naturally have been a triangular gabled roof. If a house is built like that, its eaves, which should protect the wall from rain, would instead drain rain water directly onto the wall.

At the facade of the Buddhist Chaitya caves in India, the extrados of the arch is cusped with a horn on top like the Lycian sarcophagi, while its intrados is semicircular, except for a few examples such as the Barabar cave. A semicircular shape necessarily reminds us of a 'true arch' made of piled stones or bricks. However in fact, the inside of the arch is carved as a complete wooden structure with rafters and purlins.

It must be the result of the architect's intention to build an arch form, which was brought from Persia, by means of wood, imitating only the shape of a 'true arch'. As the true arches of stone remain in the Buddhist stupa at Guldara in Afghanistan, it is evident that the arch structure had been already introduced into India. However, in India that belonged to the wooden culture zone at that time, it was not necessary to adopt the technique of arch structure, so they imported the semicircular shape only.

There are not a few pointed arch-type cave tombs in Lycian towns. Among them, the best example showing clearly the construction method of wooden architecture that must have been their prototype, is the cave tomb on the hilltop in Pinara. On the contrary, in the process of its introdution to India, Indians neglected the girder and small posts, emphasizing only the rafters and purlins that compose the outer semblance. As a result, the Chaitya caves were carved as if they were of sheer rafter structure.

The Chaitya cave at Baja that belongs to the earliest stage of Indian cave architecture shows definitely the strangeness of semicircular rafters lacking beams and posts. Conversely speaking, the interior space of an Indian cave temple enshrining a stupa should have been designed as a space with an apsidal plan and a vault-like ceiling, without exposing beams and posts, in order to match the hemispherical shape of the stupa.

As for the exterior of freestanding Chaitya temples, the facade of the Bhuta Lena cave in Junnar shows a good example. Whether the facade was made of wood or stone, large pillars and a large girder compose a square frame, and a Chaitya window is set in a back wall in the porch, and the inside is a chapel covered with a wooden barrel-shaped ceiling as an interior design.

The rock cave was produced throughout the world. The ancient rock caves in the Middle East, including Egypt, were almost all tombs, while rock cave Christian churches began to be made only after the 5th century when the Roman Empire was divided into the East and the West, as in Cappadocia.

This raises a question. Since Buddhist stupas are tumuli built over Buddha's remains, divided into small portions after his death, they are, in a sense, the tombs of Buddha. As the stupa became regarded as a typical Chaitya (object or place of worship), a Chaitya cave became a space to enshrine a stupa. In short, a Chaitya cave was a kind of a cave tomb. Why in India, where there is no custom to build tombs, were the cave tombs called Chaitya caves made in such a large number and in such a magnificent form?

There may be a possibility that, because of the transmission of the form of cave tombs in the Middle East, Indians might have begun to construct stupas as tombs and chaitya caves to enshrine them. As opposed to the Middle East, where interment was dominant for funerals, sarcophagi were not necessary in India where cremation was. Consequently, only the rock cave tombs were inherited to enshrine stupas where the Buddha's remains were embeded, and they might have come to be used as chapels as well.

Whether they are tombs or chapels, among the rock caves in the world, those with a pointed arch on the facade, moreover carved as if they were a wooden structure, exist only in Lycia and India. Indian Chaitya caves, influenced by the method of Lycian cave tombs and sarcophagi, developed on a larger scale, and created an imposing barrel-shaped interior space, setting semicircular rafters, even in true timber in certain cases, as if it was a sheer 'rafter structure', so as to match the hemispherical shape of a stupa. |

| Bibliography |