|

RIBBA GOMPA and |

TAKEO KAMIYA

|

RIBBA GOMPA and |

|

Departing from Tabo down the Spiti Valley, the national highway gets to within about 5km of the Chinese border, and then enters the Kinnaur district at the far east of the Himachal Pradesh. Due to the aftereffect of the Sino-Indian border dispute, one needs the ‘Inner Line Permit’ to travel between Sumd and Jangi even nowadays.

The Kinnaur district, which I entered in this way, is a mixed area of Buddhism and Hinduism, along with their architectural styles; occasionally a Hindu temple and a Buddhist gompa coexist in a single compound. Among numerous temples and gompas, the most intriguing one was the Ribba Gompa. Although it has not yet surveyed by the Archaeological Survey of India or reported by O.C. Handa, I was informed of the site by Shin-ya Takagi, who made a long period of journey in this area and found it the previous year.

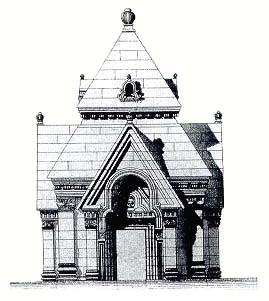

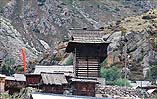

Despite being a Buddhist gompa (monastery), it is not a Tibetan type building made of sun-dried brick with a flat roof, treated in the former chapter, but a pure wooden building with a conical roof (moreover not one but two) just like Multi-Tiered Tower type Hindu temples. The Dukhan in the front is an addition from a later age, while the rear small square building is the primary temple, the façade of which unexpectedly recalls medieval Hindu stone temples in Kashmir.

Each of the temple’s façades forms a two tiered gable roof, which is seen in medieval stone Hindu Kashmir temples, such as the temple of Pandethan in a suburb of Shrinagar erected in the10th century. Here at Ribba, it is a timber structure, around which there is a colonnaded corridor (ambulatory) containing columns with Greek-like fluting as on those in the Alchi Gompa.  Hindu stone temple at Pandrethan (Kashmir)

This Ribba Gompa is also said to have been built by Rin Chen Bzang Po. If true, its first construction would have been in the 11th century. However, in contrast to the Tibetan style gompas in Alchi and Tabo, this temple noticeably holds the influences of Kashmir architecture distinct from them.

Markula Devi Temple and wood carvings, Udaipur Such influence of Kashmir architecture must have been brought here, in Himachal Pradesh; the Markula Devi Temple at Udaypur in the Lahul region, and this Buddhist Gompa at Ribba retain some vestiges of that. The original roof shape of the Ribba Gompa was probably not conical but a two tiered square type of the Kashmir style, crowned with the Amalaka-like finial now placed in the peripheral corridor. I presume that the temple at Udaypur also had a wooden square roof of the Kashmir type at the outset. If the Ribba Gompa is accurately researched and repaired by the Archeological Survey of India, it would be an important structural remnant to elucidate the history of Himachal architecture.

Having left Ribba, we carried on by jeep to the villages of Kalpa and Kothi around Recongpeo, and then we went up the Vaspa Valley after turning away from the national highway. As the lodging place was Sangla village, I visited Kamru Fort in the morning for the third time. Then we drove the jeep deeper into the south, finally reaching the last spot of the Vaspa Valley, Chitkul village, at an altitude of 3,450m.

This is a very interesting village. Religiously being in the Hindu area, there soared symbolically a square-type Hindu temple tower roofed with wooden boards, surrounded by three other temples. It was impressive to see a large cotton tree more than 10 meters high in the precinct of the Naga Temple in the rear, and the ground around the tree was covered with white cotton pieces. What interested me more than the temples however was the fact that pure wooden cabins were scattered all over the village. While the village houses and the temple tower were constructed in the "Kath-kuni" structure, piling wood and stone alternately, the cabins, with gable roofs, almost of the same number as the houses, were constructed entirely of wood. The use of these cabins was as the granaries. As this village is in near in height to that of Mt. Fuji, at an altitude of about 3,500 m, and is cut off from the outside world by snow throughout winter, they need to store crops for provisions. For that purpose they had built these granaries separately from the houses.

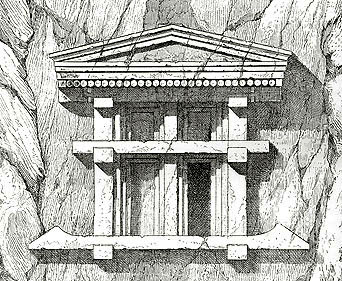

Standard granaries at Chitkul village That fact did not particularly surprise me; however my eyes were caught by their wooden construction method. Although their gabled garrets were open for haystacks, the cabins themselves were walled with vertical wood planks without windows. There were middle girders midway between groundsills and top girders, all of which were crossed at each corner by halving joints, sticking out at each end. It is the very figure of the "house type" cave tomb in Lycia, whose form had a mysterious feel about it.

I have put forward a theory ( "Lycian Influence on Indian Cave Temples" ) that the construction method of cave tombs and sarcophagi in ancient Lycia in Anatolia (now in Turkey) must have affected the Chaitya caves of Buddhist cave temples in ancient India. But I was not sure whether the middle girders that were always carved on Lycian caves were definitely reproductions of wooden buildings in those days. Surprisingly however, the very exact composition exists actually here in Chitkul.

The granaries at Chitkul have been built just as if reproducing them in wood. Their jointed groundsills are not fixed on foundations, but are simply put on stones at four corners just as if they were being carried. Leaving this grand question behind, our jeep returned to the national highway and continued on its way to Rampur by night. |