|

TEMPLE TOWERS

|

TAKEO KAMIYA

|

TEMPLE TOWERS

|

TAKEO KAMIYA

About eight years ago, I was to travel in Kashmir and Ladakh, but because of the abrupt ban on entering the Kashmir region to foreigners due to the outbreak of a dispute with Pakistan, I had to change my program and travelled around and through the state of Himachal Pradesh before going to the Ladakh region.

It was a picture of a wooden temple built in a high mountainous area, appearing as a very attractive group of buildings, the style of which I had not seen before. Two tower-type buildings stood in a courtyard surrounded with low-rise buildings, most of which were crowned with egambrel roofsf (gabled hipped roof) with concave curves like traditional Japanese buildings.

Khadaran Village and Rairemool Devi Temple The state of Himachal Pradesh, entirely mountainous and covered with cedar and pine, belongs to the wooden cultural sphere. It was a great surprise to know Hindu temples in this state were made in a unique wooden structure, like timber mosques in Kashmir.

Among the wooden buildings in Himachal Pradesh, the most interesting ones are eSquare-Towerf type temples. They are completely different from the Multi-Tiered Tower type described in the former chapter.

The etemple towerf of the Square-Tower type has many enigmas. No books have been published that have clearly elucidated its origin, function, and form. Possible reasons are that it is not easy to visit them, and furthermore, they have hardly been surveyed owing to the inconvenience of transportation, plus foreigners are prohibited from entering them, and there is a fundamental question whether they are originally religious buildings or secular ones. It can first be assumed that the temple tower is the conversion of a folk house to a high-rise building. A folk house in this region consists of two stories, the lower of which is enclosed with stable walls with alternately piled stone and timber, and the upper of which, used for dwelling has a surrounding overhanging part, like a balcony. The lower story is a space for livestock and storage, as well as the entrance.

Looking at a small temple tower near Chella, one can realize that it has almost the same principle as that of a folk house except a stairway installed outside.

At Manan, on a hill near the Durga Temple, treated in the former chapter, rises the Mananeshvara Temple. According to Ronald Bernier, an expert in wooden architecture in the Indian cultural sphere, it may be a eBhandarf of the Durga Temple, and the surrounding buildings may be a Matha (monastery) or a rest station for pilgrims.

Bhandars in Himchal Pradesh are also used to store sacred statues and eMohras.f A Mohra is a mask characteristic of the Himachal region, made of silver or brass, also called eDevataf meaning religious objects including gods. However, it is not a mask actually put on a human face, lacking holes for eyes and nose. It is opened to the public at the festivals such as Dussehra and Shivaratri, and carried to the festive place on a Ratha (palanquin shrine). Apart from the Mohra, it is hard to comprehend that a Bhandar is made more magnificent and monumental than a temple itself. In Khadaran and Sungra in particular, the Bhandar is quite prominent, looking down the whole village. Is it the same spirit as that of the Dravidian style temple in southern India, in which a Gopra (temple gate) is made greater than the main shrine?

(right) the King Shamsher Singh Although Sarahan as the name of a town or village is popular in Himachal Pradesh, there are two Sarahans that contain important temples. One is the Sarahan in the Sutrej Valley, which I will call Northern Sarahan, the other Sarahan is in the Chaupal Valley, which I will call Southern Sarahan. Northern Sarahan is located on mountainous land at an altitude of 1,920m, up precipitous roads of about 1,000m of height from Ranpur, the former trading city and capital of the Bashahr Kingdom. The Bhimakali Temple, standing majestically at Northern Sarahan, was a summer palace of the kingdom when the party of A. H. Francke made great travel for cultural research in 1909 from Shimla to Kashmir via the Kinaur and Ladakh regions. He wrote in the gAntiquities of Indian Tibeth (1914) that King Shamsher Singh of 70 years of age resided there and boasted of the beauty of his palace. Certainly this is the most sublime and attractive edifice in the Indian Himalayas. This fortress-like palace is now entirely the Bhimakali Temple.

Though the relation between the fortress and the temple is still uncertain, it was probably a theocratic kingdom and the two sides were integrated inseparably. Its temple tower might also have carried out the role of keep in the castle. On a photograph taken by Francke, there was only one main temple tower, which was connected to a smallish tower by a bridge.

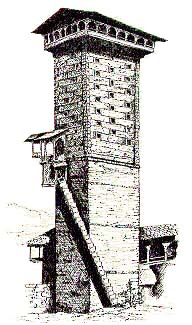

On the other hand, the temple at southern Sarahan is located far deep in the mountains, enshrining the god Bijat. Its unique composition, with an entrance to the courtyard from between two almost identical temple towers, astonishes visitors. It is said that the left tower was constructed later and the god Bijat (Vishnu) was transferred from the older right tower. Neither tower is the Bhandar but are still the temple itself, and according to M. J. Singh, they were built in a traditional method without using nails. On the way to the Ladakh region from Manali, in the north of Himachal Pradesh, via the Rohthang Pass at an altitude of about 4,000 meters, there is a small town named Gondla. It was once a trading town on a caravan route connecting India, Tibet, and the Silk Road. There remains here an old fortress from the 18th century, the form of which looks like a prototype of the temple towers treated so far. It has a residential floor on the top with a timbered overhang to four sides like a balcony, crowned with slated gambrel roof, over a grand square tower consisting of piled horizontal timber and stone tiers.

Old Castle Tower at Gondla Although one cannot currently enter it due to its poor condition, it was formerly a fortress defending this area and the palace of the local sovereign. According to the report of Harcourt in 1870, it was a six or seven storied building including large rooms with timber columns, which a hundred people could inhabit. It is said that there were two Buddhist altar rooms enshrining Buddha statues brought from Lhasa or Sigatze in Tibet. It also functioned as a watchtower.

It can be considered that the architecture of this primordial tower propagated from the Kullu Valley to the Simla Valley and Sutrej Valley and became the keeps of castles and the Bhandars of temples.

As a similar tower to that of Jogini, the Georgian dwelling houses in the long distant Caucasus region in the Middle East comes to mind. It is a fortified tower abode, which was introduced in the book gArchitecture without Architectsh written by Bernard Ludofsky. However, in spite of the efforts to search if its form was brought to the Indian Himalayas through Central Asia, I could not find any clear track connecting the two areas architecturally.

Without the purpose of defense, tower dwellings would not have been built, since simply going up and down the stairs is quite laborious, and making the lower part of the tower of stone is an indication of the principal attitude of defense. It is known by looking at reliefs sculpted on the Toranas at Sanchi that making upper floors with timber and lower floors with stone or brick was practiced from ancient times. As it is also said that ancient ruling families lived in tower-type residences, the temple tower might also succeed to the residential form in ancient India.

Incidentally, another great enigma in the wooden architecture in this region is the concave curve of the roofs. There are researchers who suppose that it is a Chinese influence, but I cannot agree, because roofs in the surrounding areas of Nepal, Kashmir, and western Himachal Pradesh are all rectilinear.

The origin of the concave curve of roofs would not reside in the influence of outer architecture but in the nature of Himachal Pradesh. That is, the concave curve of cedar trees might have been reflected in architectural forms.

I found the afoementioned Jogini (Yogini) Temple

|