|

1. CAVE TEMPLES and ROCK-CARVED TEMPLES

The first Indian cave temples were excavated around the middle of the 3rd century B.C.E. on Barabar and Nagarjuni hills in east India. They were on a small scale and an epigraph says that they were dedicated to Ajivika monks, whose sect prospered in those days, by the Mauryan king Ashoka.

It was Buddhists that contributed most to the development of Indian cave temples, excavating a large quantity on a grand scale after the late 2nd century B.C.E., such as at Baja and Ajanta.

Buddhist cave temples consisted of Vihara caves (abode for monks) and Chaitya caves (worship halls) enshrining Stupas. On the other hand Hindu caves that started later in the 5th century C.E. did not have Viharas but only shrines dedicated to their gods, tending to pursue more monumental and sculptural caves than practical caverns.

Ellora caves excavated from 6th to 9th centuries embrace groups of Buddhist, Hindu and Jain caves in an almost straight line of about two kilometers in length. Inside of them are densely sculpted statues of Buddha and his relations, the Hindu pantheon, and the Jinas (Tirthankaras) of Jainism respectively.

Among them, the Hindu caves created the most three-dimensionally formative statues assuming quite dynamic postures, and eventually carved out a huge monolithic temple in the round from a rock hillside. It is not a cave anymore so it is suitable to be called a rock-carved temple.

2. THE KAILASA TEMPLE at ELLORA

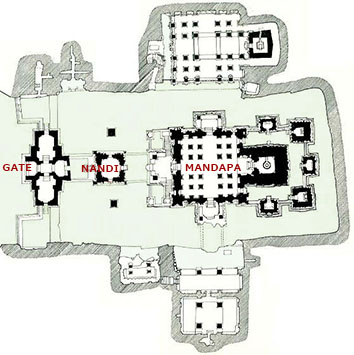

PLAN of the Kailasa Temple, 756-773 through the Rashtrakuta Dynasty,

as cave 16 in the Hindu group at Ellora, Maharashtra, India.

(From the "Encyclopaedia of Indian Temple Architecture" II-2, 1986)

Although there may have been a city here that was once called Ellapura, now this is a remote place with only the small village of Ellora nearby. The cave temples were excavated in line on the slanting surface of rock mountains, starting with the Buddhist group of 12 caves in the south, then the Hindu group of 17, and the Jaina group of 5 a little away to the north from the other two groups.

The temple that attracts our attention the most strongly is the huge rock-carved Kailasa Temple, cave 16 in the Hindu group, soaring on an overwhelming scale. Its Gopura (gateway) and Prakaras (enclosure walls) on both sides are carved out in the foreground from the rock in situ, behind which spreads a precincts as extensive as 45m in width and 85m in depth. In the center is the gigantic sculpted monolithic main shrine, the substance of which is continuous to the ground. Around the precincts, there are some subordinate cave temples excavated in the rock cliffs on both sides.

When passing through the gate, one faces a rock-carved pavilion for a Nandi (bull or the vehicle of the god Shiva) of two stories, accompanied with a colossal monumental Dhvaja Stambha (freestanding pillar) on both sides. The second floor of the Nandi Pavilion is connected to the upper floor of the gate and the porch of the main shrine by stone bridges.

The temple consists of the Garbhagriha (sanctum) and the Mandapa (worship hall) as usual. The tower-like Vimana (main shrine) containing the sanctum attains to 32m in height from the ground, so everybody who visits here holds onefs breath in its magnificence.

3. SCULPTURAL ARCHITECTURE

The Vimana of the Kailasa Temple seen from the rear mountain.

The Vimana of the Kailasa Temple seen from the rear mountain.

What astonishes visitors most deeply is that this spectacular temple complex was not made by piling ashlar but by carving directly into a rock mountain. Even though there are great stone buildings all over the world, especially in the Middle East and Europe, such a huge example, which was carved into a rock and is continuous to the ground, is never seen other than in India. Moreover its walls are entirely carved out with mythical scenes, Hindu gods, fanciful animals, and architectural elements, and its interior has formally carved columns and beams as if it were a stonemasonry edifice.

Rock-carved temples of this sort began in the 7th century in Mahabalipuram in south India, spreading subsequently throughout India such as at Masrur in the north, Damnar in the middle, Karugmalai in the extreme south, and eventually the Jain temples at Ellora. This fact indicates that Indians loved sculpture most of all formative arts and were not fully satisfied with cave temples as caverns without sculptural exterior.

When broadly classifying world architecture into three: the membranous, sculptural and framework architectures, Indian stone architecture that developed greatly in mediaeval times can be substantially called sculptural. It can be said that rock-carved temples above all most remarkably represent the Indian spirit in its desire to make even architectural works as if they were sculptures.

4. CONSTRUCTION METHOD

A sculpted wall of the Kailasa Temple at Ellora

A sculpted wall of the Kailasa Temple at Ellora

One would feel faint thinking about the awful amount of labor to necessary carve out an edifice of as high as 32 meters by hand from a rock mountain to perfection, but actually it can be considered that it was technically easier and more economical than the construction of a stone building of the same scale on the ground.

First of all, in order to construct a stone building it required immense cost and labor for cutting out ashlars in a quarry and transporting them to the building site. Then at the site masons had to chisel the ashlars into accurate shapes based on the detailed temple design, set up scaffolding to carry them up to high positions, and assemble them exactly in using tenons or clamps.

Compared with this, it was much more economical in terms of labor and expense to cut out a huge mass from a rock mountain and sculpt it into an colossal temple in situ. Moreover, it did not need the high technology of combining ashlars so tightly to be able to endure earthquakes.

For a stone building ashlars were piled up from the bottom to the top, while in a rock-carved temple masons carved out a temple in the opposite way: from the top to the bottom. From the beginning, cave temples were excavated in that way, in order to work without scaffolding and thus lower costs.

The construction work was usually divided into two stages, those of masons and sculptors, but in this case, both must have been done together at the same time. Since rock carved temples were completed in a rather short time, the sites would have always been crowded with a great number of workers.

5. DIFFUSION of THE SOUTHERN TYPE TEMPLE FORM

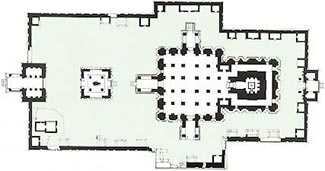

PLAN of the Virupaksha Temple in Pattadakal, 745 of the Early Chalukya Dynasty

(From "The Hindu Temple" by George Michell)

As cave temples were only small caverns cut into enormous rock mountains, columns and beams had no actual role in a structural point of view, being nothing but replicas to make them look like true edifices imitating real independent buildings on flat land. However, at the rock-carved temples in the round, pillars and girders must have sustained real loads, so the workers must have estimated the thickness of each member.

In order to accomplish such a huge rock-carved temple as the Kailasa Temple without failure, with much higher level of technology than in cave temples, there must have been architects who were able to conduct every kind of workers, possessing structural knowledge and imagining the final figure of the magnificent temple. Despite not knowing the name(s) of the architect(s) of the Kailasa Temple, he was bound to be from southern India.

The reason is that the Kailasa Temple at Ellora is in the style of the south Indian type, and moreover a stone temple, after which the Kailasa Temple was modelled, exists in Pattadakal, the city of the Early Chalukya Dynasty.

In mediaeval south India the Pallavas and Chalukyas were destined to always be in confrontation with each other, while the Rashtrakutas in the Deccan assumed hegemony in southern India in the middle of the 8th century, acquiring at the same time a mastery of those two dynastyfs cultures.

The Chalukyans took the capital of the Pallava Dynasty, Kanchipuram, and used its masons and craftsmen in the construction of the temples in Pattadakal. It can be supposed that furthermore the Rashtrakutas brought those architects and craftsmen to Ellora.

6. THE RASHTRAKUTA DYNASTY

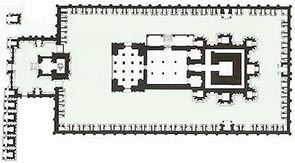

PLAN of the Kailasanatha Temple in Kanchipuram,

early 8th century during the Pallava Dynasty.

(From "The Art of Ancient India" by Susan L. Huntington, 1985)

According to an inscripition left at Ellora, it was the second Rashtrakuta king, Krishna I (reign 756-773), who completed the Kailasa Temple. When he participated in the campaign by which his father, the former king, Dantidurga, defeated the Chalukyas, which was a very advanced country in terms of culture at that time, Krishna seemed to have been affected by their architecture, especially by the Virupaksha Temple in Pattadakal (745).

After succeeding his father to the throne, he ordered the Kailasa Temple at Ellora to be carved out three and a half times larger than the model in Pattadakal. As he was able to accomplish it during his reign, the temple was called the Krishneshvara Temple after his name in those days. It indicates that such an enormous temple was completed within as short a period as only 17 years, showing how efficient the making a rock-carved temple could be in comparison with a stone temple.

When comparing the plans of both temples, one can find they are almost the same, composed with a gate, a Nandi Pavilion, a Mandapa with three porches, and a Garbhagriha encircled with a circumambulatory gallery, even the same number of pillars.

However, the setting up of sub-shrines around the gallery was the influence of the Pallava temple of Kailasanatha in Kanchipuram, after which Chalukyan temples were modelled. The sacred Himalayan mountain Kailasa was believed to be the abode of the god Shiva, so temples with this name all enshrine Shiva and symbolize that sacred mountain by its soaring Vimana.

7. THE COMPOSITION OF VIMANA

Interior of Cave 16, the Kailasa Temple, Ellora

Interior of Cave 16, the Kailasa Temple, Ellora

The main shrine itself of the Kailasa Temple stands on a high podium of two parts, the upper Adhisthana and the lower Upapitha, around which is sculpted a line of large elephants. Access to the main floor is through staircases on either side of the main porch. In the extensive interior of the Mandapa are 16 independent pillars and 20 pilasters carved on the walls. Since light comes in only through the openings of entrance and balconies on both sides, the hall gives an impression of a dusky solemn forest of pillars.

On the rear is an Antarala (small antechamber), then the Garbhagriha (sanctum) where is enshrined a Linga (phallus) symbolizing Shiva. A Garbha means a womb in a female body as the source of life, and this space is the center of the temple.

Over the thick wall surrounding the sanctuary soars the pyramidal tower of the Vimana with stepped stories in a figure of the Southern Type, surmounted with a large dome-like crown stone on the top. Further on the top was a pitcher-like finial, now lost, which was called a Stupi in southern India, while in northern India a Kalasha, which was derived from the sacred mountain Kailasa.

The invisible vertical line that penetrates from the Linga to the finial is interpreted as an axis of the universe that connects the earth for men and the heaven for gods. Together with carvings and sculptures throughout, both in and out, Hindu temples, it indicates that they are eHouses of the Godsf where heavenly gods reign.

|