|

WILLIAM SIMPSON |

TAKEO KAMIYA

|

WILLIAM SIMPSON |

|

It was the 19th century Scottish painter, William Simpson (1823-99), who first brought Himalayan architecture in detail to the attention of Europe. Having mentioned his name several times in this web site, I will narrate here his life in more detail, especially in relation to Himalayan architecture.

William Simpson was not only an excellent 'reportage painter' but also a writer of many monographs and books on architecture and archaeology. The reason I used an unfamiliar word ‘reportage painter’ is that, in the 19th century painters carried out the current role of ‘news photographers’ and particularly he became famous through his reportage of the Crimean War from the battlefields, even be coming celebrated as ‘Crimean Simpson.’

It can be said that Simpson spent all his life travelling around the world, witnessing major wars and events all over the world in the 19th century, and also attended various memorial celebrations, being personally close to the British and German royal families. Although he presented many articles and treatises to academic societies and associations, such as the RIBA (Royal Institute of British Architects), he had hardly received any formal education in his childhood. He lived completely freely, studying by himself, drawing and painting, publishing books, and was widely known in society in those days.

He was a Scot, born in Glasgow 15 years later than the great architectural historian, also Scottish, James Ferguson. (Subsequently, Simpson would become intimate with him, being deeply influenced by Fergusson to study Indian architecture.) As Simpson’s family was too poor to send him to school, the only formal education he received was for 15 months from the age of eleven while he was looked after by his grandmother in Perth. While mastering the technique of lithograph, Simpson eagerly went to free introductory lectures at the Mechanic’s Institute and Andersonian University that were near the studio, and he went to libraries to avidly read books. He even attended an evening class in architectural and mechanical drawing at the Andersonian University from the winter of 1838 to the next year.

In 1840 he transferred to Allan and Fergusson's atelier, contracting to work as an apprentice for seven years. During that time, he took lessons in painting and design, attending the evening school of a newly established school of arts, the Glasgow School of Design (the future Glasgow School of Art), in which Charles Rennie Mackintosh would be a student about 40 years later. When he reached the age of 27 in 1851, he moved from Glasgow to London to obtain higher techniques in lithography. It was just the year that the first great Exhibition was held in London. He was able to get a job in the firm of Day and Sons', which was a renowned, excellent lithograph studio inaugurated by Day, who had been dead some years, and managed by his three sons in cooperation. It was the age, when the photoengraving had not yet developed and the method of illustrations on books and magazines had shifted from etching to lithography, which was in its heyday, though it would be superseded by wood carving 20 years later. Day and Sons’ were very busy this year thanks to the works for the world's fair.

It was the Crimean War, which started in 1853, that brought a turning point to the life of Simpson, who had improved his skill remarkably on lithography and watercolor painting. It was a war on a large scale, which continued as long as three years, over the dominium of the Middle East and the Balkans between Russia, who took the strategy of pushing southward, and the allied forces of Britain, France and the Ottoman Empire, who intended to obstruct it.

He did not miss this chance and went to the Crimea. Experiencing shellfire at first hand, he resided there for a year from that winter, sending his watercolors depicting the sights of battle fields to London for the British newspapers.

The next military engagement that Britain confronted after the Crimean War was the rebellion of Indian soldiers against Britain, called the ‘Indian Mutiny.’ Taking the opportunity of the revolt of sepoys (mercenaries of British India), Indian soldiers and peasants rose against the ruling East India Company, crowning the Mughal Emperor at their head. This ‘mutiny’ continued for two years from 1857 in various districts in India.

Day and Sons’ planned to report visually the state of India after the Mutiny, and requested Simpson to be their correspondent. Simpson, who had long been interested in the Orient, planned on this occasion to travel extensively throughout India and draw everything of its culture, geographical features, customs, and religions.

Close to ten years before that, David Roberts, also a Scottish painter, made a grand tour (1838-39) through Palestine, as the birth place of Christianity, to Egypt and completed the publication of five volumes of a large-sized book of lithographs entitled “The Holy Land” which was praised with great admiration. It was an excellent book of paintings consisting of 123 plates in total, in the form of lithographs colored by hand; a masterpiece in the history of lithography.

Since the 18th century, many British landscape painters had already sailed for India and painted its exotic scenery in various methods, such as watercolor, oil painting, lithography, and etching, to introduce them to British society.

After he landed in Calcutta in October 1859, he travelled in India for as long as two and half years, untiringly drawing on his sketchbooks everything he saw, like buildings, ruins, townscapes, people’s figures, and landscapes. He went to Delhi by train, on the railroad that had just inaugurated, to meet the Governor-General of India, Canning, and his wife. Simpson attended all the Viceroy’s official events, drawing those sights, and became painting teacher to Lady Canning who loved pictorial art.

In an age when transportation was not as convenient as now, Simpson explored hinterlands, getting on a ‘Dooly’ (simple palanquin without a roof) carried by Indian coolies, and drawing natural objects and buildings in regions which the British had not looked at, referring to this, in his phraseology, as ’True India.’

When returning to England in 1862, Simpson started to produce works of full-scale watercolor based on the sketches that he had accumulated in India. It took four years to complete a total of 250 plates, preparing the publication of a book of pictures in four volumes in the form of chromolithography, handing them over successively to Day and Sons.’

As 50 watercolors among the 250 had already been transferred into lithographs, these came to be published as two volumes of a large-sized book of pictures under the title of “India Ancient and Modern.” However, since competent lithographers had already left Day and Sons,’ the quality of these lithographs never satisfied Simpson.

Though intensely discouraged, Simpson was able to get a commission for a new job. It was an article in “The Illustrated London News,” the world’s first weekly graphic newspaper; Simpson was to be a ‘special artist’ to draw the Prince of Wales’ tour to attend the marriage ceremony of the Tsarevich, the subsequent Emperor of Russia Alexander III, in St. Petersburg, Russia. With this as the start, he would be dispatched as a freelance reportage painter to various spots in the world for The Illustrated London News at every important event or celebration, and his paintings, transferred to woodcuts, would adorn its pages.

In 1868 Simpson went to the scene of the Abyssinian (Ethiopian) War for reportage, and then travelled through Egypt to Turkey until the next year, attending the inauguration ceremony of the Suez Canal. He became a permanent staff member of the newspaper that summer.

The next year he was requested to report on the Prince of Wales’ tour to China for his attendance at the marriage celebration of the Emperor of Qing. Availing himself of this opportunity, Simpson planned an around-the–world trip.

After his first journey in India, he made the acquaintance of the architectural historian, James Fergusson. Fergusson showed interest in his itinerary and recognized its value as material on the history of Indian architecture, particularly his sketches of the Himalayan region and Kashmir, and recommended him to give an account to the RIBA (Royal Institute of British Architects). From then Simpson became a contributor of reports and essays on his experiences to the transactions of the RIBA, RAS (Royal Asiatic Society), and so forth. Among his numbers of writings including his autobiography, apart from the books of pictures, what was reprinted long afterward in the U.S.A. is the book entitled "The Buddhist Praying-Wheel." Though the title includes ‘Buddhist,’ it is a book pursuing the symbolical meanings of circular motifs in various religions in the world, starting from the ‘Mani wheel’ in Tibetan Buddhism, researching their origin in images of the sun. He carried out travels in the Indian sphere four times in total, among which the second one was from 1875 to 76, accompanying the Prince of Wales, hunting tigers together in Nepal. The third one was from 1878 to 79 mainly for the reportage of the Afghan War, which was the warfare between Britain, who desired to rule Afghanistan, and Afghan Guerrillas, similar for Britain to the Vietnamese War a century later for the U.S.A.

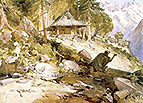

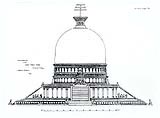

While executing such reporting journeys, which continued up to his old age, holding an interest in architecture and archaeology throughout his life, he would always make time between assignments to visit antique edifices and ancient ruins. In Afghanistan he found the Stupa of Ahin Posh near Jellalabad and excavated it through the cooperation of the army, unearthing a receptacle containing ashes and coins from its central part. He drew up a reconstruction after returning to England. Among his many writings, the most important one might be "Origin and Mutation in Indian and Eastern Architecture" published in the Transactions of the R.I.B.A. but I am most interested in his "Architecture in the Himalayas," in which he narrates his three journeys to the Indian Himalayas, twice for six months each and a three month expedition from Shimla to Chini (currently kalpa) with the party of Captain Evans. The article includes fair copied fine sketches of Himalayan architecture.

An especially excellent one among them is a sketch of a temple standing at Chergaon in the Satlej Valley, which was reprinted in Fergusson’s revised edition of the "History of Indian and Eastern Architecture," so it became well known by later people. Its ‘picturesque’ figure is counted one of the best pieces of Himachal architecture. However, none of the books on Himachal architecture published since then have included any single photograph of this temple. Whenever the temple at Chergaon is mentioned as an example of Himalayan wooden temple architecture, this sketch by Simpson has been reprinted at all times, almost as if this temple does not exist anymore.

As a result of thinking about this, together with looking in detail at Simpson’s itinerary, I surmised that that temple must be the current Maheshwara Temple at Sungra. In the book “Antiquities of Indian Tibet” written by A. H. Francke, who carried out a great research tour from Shimla to Shrinagar about 50 years after Simpson, there are placed only photos of the temple at Sungra without any reference to Chergaon. This fact can also be considered an endorsement of my conclusion.

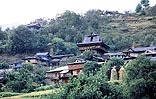

Temple at Sungra, old and new

Even so, there was still a question; while the temple at Sungra is entirely covered with carved wooden panels, on Simpson’s sketch it is not, furthermore the total proportions of both temples seem a little bit different. In addition to that, I had not heard that the village name, Chergaon, was an ancient designation of Sungra.

It is a Simpson’s sketch on location and I came to know that the foregoing sketch is one tidily redrawn for publication. In this sketch, I noticed, a little surprisingly, a Square-Tower type bhandar depicted behind the temple. At Sungra, there is no space behind the temple for a bhandar because of its location directly facing a precipitous ravine at the rear. Then, are the temples at Chergaon and Sungra utterly discrete from each other, or did Simpson assemble two buildings into one drawing for fun? I worried whether the illusionary temple at Chergaon had really been lost or not.

There is a small town named Chirgaon in the east of Rohru, upstream of the Pabbar River; I wondered if Chergaon that Simpson visited would have been this Chirgaon. In order to resolve this long embracing question, I extended my journey to this town, but everyone asserted that there was no such temple in the town.

Not able to reach the aimed temple by car, I asked a villager to guide me in walking there in almost complete darkness, and eventually we arrived at the Kantu Devta Temple at Devidhar village that I had seen some time ago in the distance. I underwent a deep feeling of frustration, not being able to find the illusionary temple of Chergaon after all.

Incidentally, at almost the same time I started this journey, Shin-ya Takagi also headed off toward the Himachal region to spend three months travelling on foot. When I asked him about the outcome of his trip, he surprised me by saying that he had identified the temple of Chergaon, not in the Pabbar Valley but in the upper Satlej Valley, near Sungra.

What Mr. Takagi heard from villagers is that there are three brother temples around there: the eldest brother temple is at Sungra, the second elder is at a village named Katgaon (said to have been reconstructed after destruction by fire in 1971), and the youngest is this temple at Chagaon. All of them enshrine the same god Maheshwara (Shiva) and were constructed in the same style. It is difficult to tell them apart from only their sketches depicting temple forms instead of photos, since they are entirely made of cedar as far as their roofing and finials. As a result of that, the long obsessing problem for ten years has been at last resolved and the illusionary temple has become an actual temple, proving the accuracy of Simpson’s sketches. I am quite impressed looking at the photograph of the actual village and its temple how just it is the same as the skillful sketch that Simpson made a century and a half ago.

William Simpson is not as famous as Thomas Daniel or William Hodges among the British painters who painted India, due to the fact that his great book of pictures of India did not materialize. In spite of that, I am convinced that he was an excellent artist depicting Indian architecture and scenery more accurately and poetically than any other painters, through his profound knowledge of architecture and his gifted talent for exact sketching.

In 1893, when he was 70 years old, a world’s fair was held in Chicago, in which young Frank Lloyd Wright was deeply impressed by an exhibition of Japanese architecture. Simpson was asked to sail to Chicago and report on the fair, but he was dissuaded by his doctor because of his advanced age. After that he spent the remainder of his life quietly with his wife, a portrait painter, and his only daughter, Ann Penelope.

|