|

WOODEN ARCHITCTURE

|

TAKEO KAMIYA

|

WOODEN ARCHITCTURE

|

TAKEO KAMIYA

The style of the wooden architecture in the pluvial Kerala region, which faces the Arabian Sea, can be called the ‘West Coast style.’ Its northern limit extends to a little beyond the border of the current state of Kerala, viz. Mangalore in the state of Karnataka, at the end of the Western Ghats mountain range. Further north is an area of little-rain and the style of wooden temple architecture is replaced by that of stone temples in the Deccan.

A temple located just on the boundary between them is the Chandranatha Temple in Mudabidri, which belongs to Jainism, still surviving in this region. This great temple built in the 15th century certainly intermediates between those two architectural styles, having an upper wooden story with a sloping timber roof covered with copper over the ground stone story with roofs of stone slabs. Although its first floor is made of stone, the structural system is an utterly wooden-like one, simply replacing timber columns and beams with stone. As there are brackets carved in the images of gods under the wooden roofs, similar to Nepalese wooden temples, some historians insisted that the architect must have been Nepalese. However, this is dubious, because it is improbable that an architect was invited all the way from Nepal where the Jainism faith did not exist. Furthermore, as explained in the former chapter, decorative gables are uncommon in Nepalese architecture. There are remains of a small wooden palace from the 17th century in a southwestern suburb of Mudabidri. The wooden columns, with delicate carvings in its open hall facing a courtyard, rather resemble the wooden carvings on columns in wooden temples in Sri Lanka.

There is a greater wooden palace complex in Padmanabhapuram, in the opposite direction of Mudabidri, a little south of the state of Kerala. This town, meaning ‘a city born from a lotus flower,’ was the old capital of the princely state of Travancore. Here the wooden palaces reconstructed by King Marthanda Varma in the 18th century remain intact.

As it is now in the territory where the Tamil language is spoken, this area is incorporated into the state of Tamil Nadu. However, all buildings in this palace precinct, except the royal stone oratory, were constructed of wood in the West Coast style of Kerala.

When entering a forecourt through the main gate for a start, one would be taken aback by the appearance of the compound, looking just like Japanese architecture: most of the buildings lying ahead are made of plain wood of teak and crowned with tiled gambrel roofs (gabled hipped roofs). The building with two audience halls of the Mantrashala and Poomukham stacked one on the other are especially worth seeing. The wooden carvings within its gable have quite different patterns from those of temples.

The interior of the Poomukham on the second floor plainly shows its principal structural system: four freestanding columns support four beams demarcating a square coffered ceiling, on which rafters lean to the peripheral girders.

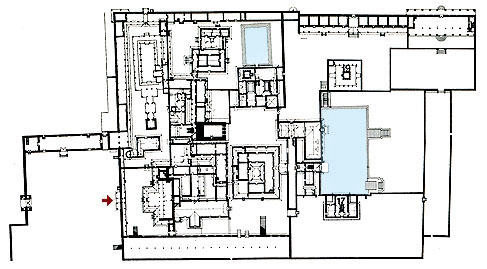

As shown in the plan this palace consists of numbers of comparatively small buildings with courtyards and gardens. However, there are no axes here that penetrate the entire compound, nor geometrical Chahar-Baghs (four quartered gardens) as in Mughal palaces, nor a Mandala-like composition in the site-plan.

A Capital in Thaikottaram and an oil lamp in Mantrashala

The Kerala region had been connected with the western world through maritime trade since ancient times. Judaism was brought here as early as in the 1st century CE and Christianity and Islam followed it. In Kochi (former Cochin) there remains a Jewish synagogue and Christian church of St Francis, which retains the gravestone of Vasco da Gama.

A legend says that one of the twelve apostles, St Thomas, came to southern India for missionary work, but there is no historical evidence. However, it is certain that Christianity was brought to India before the establishment of the Roman Catholic Church; Masses in ancient Hebrew have been consecutively handed down even to now.

On the other hand, the earliest Islamic mosque built in India is said to be the wooden one in Kodungallur. An inscription in the place says that it was constructed in 629. If so, it is far earlier than the first mosque in Delhi from the 12th century, or the Qutub Mosque. As that date indicates a time immediately after the birth of Islam, the story is incredible and the current mosque is quite new.

A mosque of the most imposing appearance in Kerala is the Miskar Mosque in Kozhikode (former Calicut) that was first built in the 17th century. Although it has not reached so high a degree of perfection as wooden mosques in the Kashmir region, which will be treated in the next chapter, Multi-Tiered mosques with a gabled roof are very rare even in the vast Islamic world. The tradition of such wooden architecture continued without distinction between religions. The state capital, Trivandrum, has a university, the old buildings of which are made of brick with wooden roofs, and the Napier Museum, designed by the British architect, R. F. Chisholm, adorned with fine traditional wooden sculptures and carvings.

What is especially interesting among wooden architecture in Kerala is the ‘Kutambalam.’ It is a kind of theater, which stands in the precinct of a large Hindu temple, for the performance of religious dramas called the ‘Kutiyattam’ on festive days, and occasionally of traditional music and dance. From the outset in India, since festivals and assemblies were usually performed outdoors, theaters have not existed. So it is not clear why it came to be erected only in Kerala. According to G. Panchal, there are Kutambalams in 16 temples. The one with the highest degree of perfection and the grander scale among them is that of the Vadakkunnatha Temple in Thrissur.

However, all extant Kutambalams were constructed or reconstructed in the 18th or 19th century and the form of those erected before is unclear. That is, the structural system of those extant Kutambalams is completely different from that of traditional Indian architecture and is quite characteristic as to be supposed to have been developed in early modern times.

The component distinguishing the external appearance of Kutambalams in temples such as Thrissur and Irinjarakuda is a great hip roof covered with copper or tile. It is quite interesting that in their huge inner spaces there is a fixed stage with its own roof, which is supported by round columns of teak, as ‘a building within a building’ similar to the formalized stage with four columns for the traditional Noh drama in Japan.

Goverdhan Panchal, an Indian stage designer, researched and published a book on Kutambalam, appreciating it as the Indian traditional theater form in contrast to the European theater with a proscenium stage.

Incidentally, the only example in which such a structural system is used is, so far as I know, the Entrance Mandapa of the Nellaiyappar Temple in Tirunelvelli in southern Tamil Nadu. One can only speculate on the origin of this wooden structural system.

It is a little known fact that violins are played in Indian traditional music in southern India. Western violins were brought to India through maritime trade from early times and became almost a traditional ethnic musical instrument by applying it to Indian traditional tuning and methods of rendition. |